BY Donna Parham

Photography by Ken Bohn

At the Zoo, even snakes have regular doctor appointments. That’s why senior keeper Tommy Owens spent the morning at the Zoo hospital with two deadly pit vipers.

TLC FOR A SNAKE

Reptile keepers at the Zoo are trained to safely provide medical care for even the most dangerous snakes in their care.

Zoo veterinarians and vet techs drew blood, took x-rays, and did a thorough physical examination, pronouncing the patients—juvenile Mang Mountain pit vipers born at the Zoo in 2017—fit and healthy. But how, you might wonder, does one provide a venomous pit viper with such care? General anesthesia is involved, but it turns out that immobilizing a snake addresses only part of the safety concern.

WATCH THOSE HANDS

“Their fangs are just as dangerous [under anesthesia] as when they’re awake,” says Tommy. “We have to make sure that we—and the vets and vet techs—keep their hands a safe distance from those fangs.” Although most people would shy away from getting so close to dangerous snakes, Tommy and the other reptile keepers are well trained; they know exactly how to do it safely. “When we’re working with a venomous animal, nothing else exists,” he says. “We are focused 100 percent on what we are doing at that moment.” Good thing, because a mere scratch from one fang could cause lethal consequences.

IT’S THE PITS

Pit vipers—which are found in Asia and the Americas—are stout-bodied, large-headed snakes. They are named for a pair of pits that lie on each side of the head, between the eye and the nostril. Within the pits are unique, heat-sensing organs—the most advanced of any species. At close range (within about 40 inches, or 100 centimeters), a pit viper can detect a temperature difference of even 0.1 degree Fahrenheit.

FEEL THE HEAT

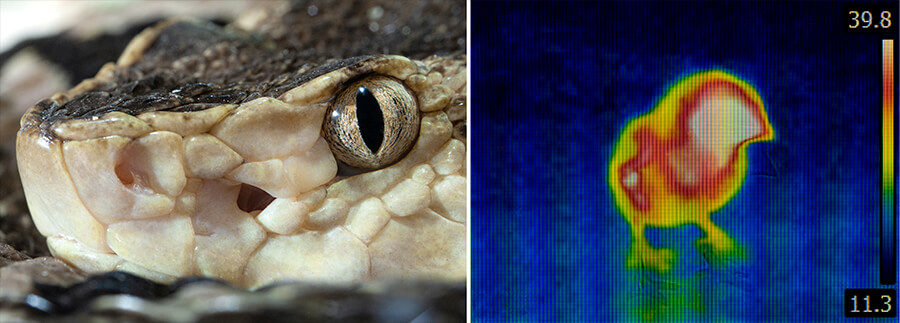

This Brazilian lancehead Bothrops moojeni can “see” a heat image of its surroundings, thanks to a pair of heat-sensitive pits that lie on each side of the head, midway between the eye and the nostril.

When the pits detect heat, nerves transmit detailed information to the same area in a snake’s brain that interprets visual images. This gives the snake a three-dimensional “picture” of its surroundings. And, a pit viper can perceive and orient on a heat image of prey, even in total darkness. Because we lack this adaptation, one way to imagine what that might be like is to compare it to an image captured by an infrared camera.

GOTCHA!

Pit vipers are ambush predators—they lie in wait for their meals to come to them. Coiled up in the brush or under a rock or log, a snake can go long periods of time without moving. Cryptically colored, it blends in with its surroundings.

SNAKE SCALES

A snake’s scales may look like individual structures, but they are connected parts of a continuous layer of skin.

When an unsuspecting rodent scurries by, the snake strikes, injecting potent venom with its long, retractable fangs. And then, the snake releases the injured rodent. Not until the wounded animal stops moving does the snake swallow it—whole, and without risk of injury from the prey’s sharp claws and teeth. By ambushing prey instead of chasing it, a reptile conserves energy. It also reduces the risk of encountering a predator—such as an owl, a king snake, or a mongoose—becoming a prey item itself.

BABY BOOM

“We’ve been very successful in reproducing pit vipers, and we’ve had a lot of firsts, as well as multiple generations,” says Tommy, naming the Mang Mountain pit viper Protobothrops mangshanensis, Guatemalan palm pit viper Bothriechis aurifer, side-striped palm pit viper B. lateralis, and Rowley’s palm pit viper as examples.

BOUNCING BABY SNAKES

The San Diego Zoo was the first place Mang Mountain pit vipers hatched outside of the wild—thanks to a female that was already gravid (“pregnant” with eggs) when she arrived. When one of these original offspring laid eggs that hatched, keepers were even more excited; it meant that the rare snakes had successfully bred in managed care for the first time ever.

He admits it’s often “difficult to breed pit vipers, because some babies come out wanting to eat tiny little frogs.” The trouble is, frogs aren’t commercially available as a food source, so mice must suffice. “Keepers have to coax the newborns into eating minute pieces of mice,” Tommy says. “They can’t be rushed. It’s a patience thing—and it’s a special kind of keeper who can do it.”

BABY BLUE

Juvenile Mang Mountain pit vipers have bright blue tail-tips. They may wiggle their tails to attract prey that doesn’t even see the otherwise-cryptic snake.

One of these special keepers is Erika DiVenti, who has helped raise dozens of tiny pit vipers at the Zoo. She acknowledges that it takes determination. “Being able to sit very still for long periods of time with a prey item is the hardest, but any sudden moves can make them drop their food,” she says. “When a baby finally eats on its own, it is a true feeling of accomplishment.”

SNAKE SOJOURNS

Pit vipers inspire awe, but they can also inspire fear. The fact is, many of us live in rattlesnake country, and rattlesnakes are our native pit vipers. To stay safe around your home, Tommy suggests removing the snakes’ food sources—rodents such as gophers and mice—as well as wood piles. “Snakes can smell people—and dogs—which they avoid,” he says. He acknowledges that “you might see one passing through your yard from time to time.” What to do when a rattler takes a rest break on your porch? “Leave it alone,” says Tommy. “You can’t get bitten if you’re not close to it, and without a source of food, it will be gone within a few hours.”

AT THE ZOO

You can safely come within inches of pit vipers at the Zoo. It’s home to two species of Asian pit vipers—the Chinese mountain viper Protobothrops jerdonii xanthomelas and the Mang Mountain pit viper —and 18 species of New World pit vipers including 11 rattlesnake species and 2 species of bushmasters, the world’s largest pit viper species. Rare in zoos, the mysterious bushmasters are also rarely encountered in the wild.

IN THE WILD

Animal care manager Brett Baldwin’s considerable experience with bushmasters at the Zoo made him a valuable member of a research team that set out to document exactly where the black-headed bushmaster Lachesis melanocephalus can be found in its tiny range in western Costa Rica. Brett and his team spent two weeks in search of the snakes, pushing their way through the thick rain forests of Parque Piedras Blancas. You can read his blog about the experience here.

SHAKE, RATTLE, AND ROLL

A rattlesnake adds a new segment to its rattle each time it sheds its skin, and the interlocking parts fit loosely together. When the snake shakes its tail, the segments rattle together, making a distinctive buzzing sound. The larger and longer the rattle, the louder the sound.

When you’re enjoying the wilderness, consider yourself fortunate if you happen to spot a “rattler” or other native snake. Just keep your distance. A little care in where we put our feet—on established trails and away from brush—is all that’s necessary for us to peacefully coexist with these fascinating reptiles.