BY Donna Parham

Photography by Tammy Spratt

Penguins get all the glory. Sure, they are adorable, and their Cape Fynbos home in Conrad Prebys Africa Rocks at the Zoo is an amazing place to watch them zip through the water. But Africa Rocks is home to another themed bird exhibit that is also wowing visitors.

PERFECT PLACEMENT

In a clump of grass less than a yard from the pedestrian pathway—perfectly placed for visitors to view—a Namaqua dove broods her growing chick in the nest.

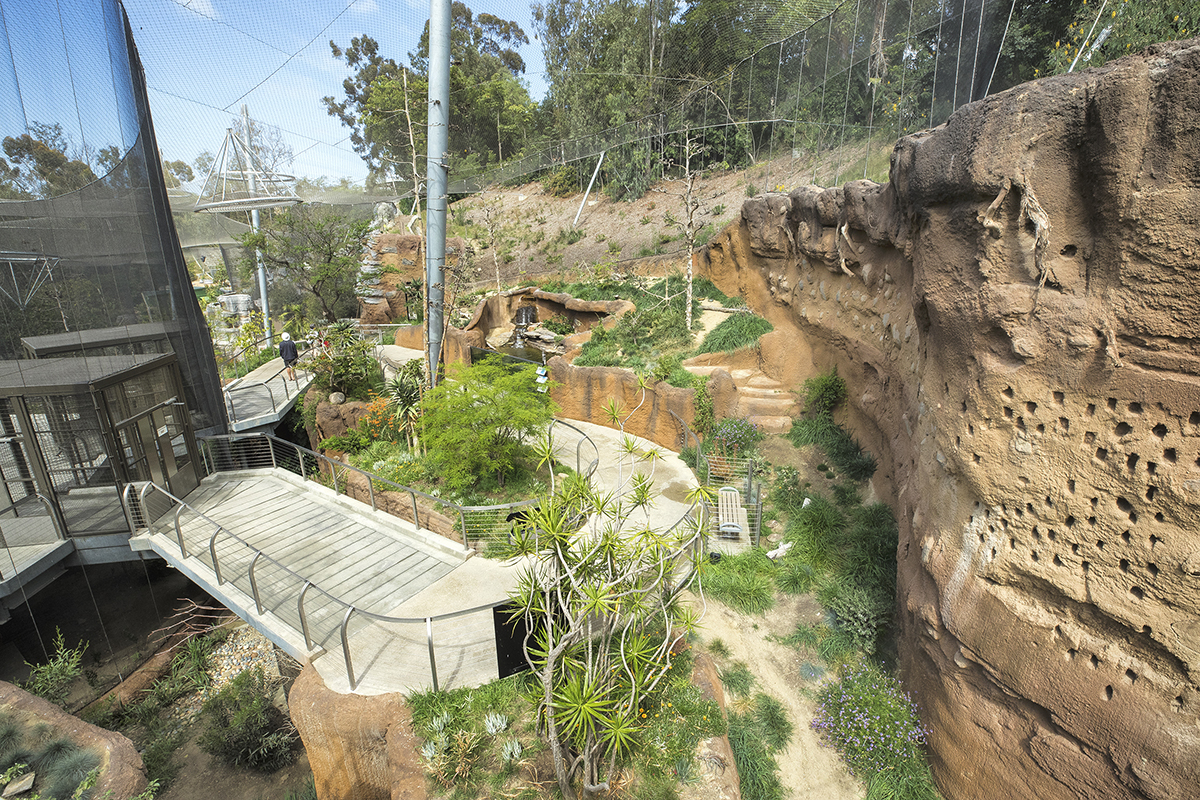

The immersive new aviary in the Acacia Woodland area recreates a piece of African savanna, with grasses, acacia trees, flowering shrubs, and a flowing watercourse. The authentic habitat provides the opportunity to display a large variety of of birds, including quite a few that are new to the Zoo. To the delight of visitors and keepers, “the birds are responding to the environment we’ve created, and we’ve been seeing some incredible behavior,” said Dave Rimlinger, curator of birds, San Diego Zoo. “The aviary is really popular with photographers,” he said. “They’ve taken some fantastic pictures.”

FLASH OF COLOR

Purple grenadier finches are a dazzling species in the aviary.

C’MON IN

From the upper platform, you might find yourself looking into the coral-tree nest of a magpie mannikin, or spy a male pin-tailed whydah displaying to a female. Or, you might find a golden-breasted starling intently observing you from her eye-level perch on a tall aloe stalk.

STEP INSIDE

The upper platform gives you a “bird’s-eye view” of the entire aviary, and a close look at the cliffside nest sites of bee-eaters, doves, and finches.

The lower trail meanders through grasslands, acacias, a running stream, and ponds where African pygmy geese paddle. Stone partridges scurry across the path, and white-bellied go-away-birds call stridently as an unconcerned black-headed weaver flutters, bathes, and drinks in a sunny, shallow waterway.

PRETTY BIRD

The emerald-spotted wood dove sports a dash of verdant green.

HOME-MAKERS

Senior keeper Anne Clayton said that her biggest surprise since the exhibit opened has been “seeing how quickly the birds became comfortable in their new home and started nesting behavior—those are really good signs.” She said, “When you have the opportunity—like with this exhibit opening—you look at years of experience, and ask what worked, what didn’t, and then you integrate best husbandry design.”

HOME, SWEET HOME

White-headed buffalo weavers build nests year round, because they roost (sleep) in them. “They build nests with sharp, thorny twigs around the edges, to protect it from other birds,” Anne said.

Within months of the aviary opening, many species—including black-headed weavers, Fischer’s lovebirds, and emerald-spotted wood doves—built nests, laid eggs, and raised chicks to fledging. “We like to get our hands on juveniles as soon as we can, to band each one with a unique color combination that identifies them,” Anne said. “And we do a quick health assessment; we get a weight, look at their body composition, and pull a few breast feathers to submit for DNA sexing.” The entire process takes less than five minutes.

THIS ONE WILL DO NICELY

A male red-cheeked cordon bleu selects nesting material.

IF YOU BUILD IT, THEY WILL COME

Anne has worked with many species of African birds, but her current favorite in the aviary is a species that’s new to the Zoo: the black-headed weaver. Their globe-shaped, neatly woven structures dangle like oversized Christmas ornaments from the spreading branches of a camel thorn acacia tree.

SAVANNA TREE

The spreading branches of a camel thorn acacia tree provide perching spots for many birds and the perfect nesting habitat for black-headed weavers.

Males weave spherical nests with long strips of palm leaves, and keepers make sure there’s a supply of fresh fronds in the aviary. Nibbling at the base of a green palm frond, a bird grasps a piece of the tough plant material in his bill. Then, he flies toward the tip of the frond, “unzipping” a length of sturdy fiber that’s just right for home construction. A nest-building male stops every so often to put on loud, colorful displays intended to entice house-hunting females. When she spots a nest—and a male—that piques her interest, the female flutters up to have a look inside. If she fancies it, she moves in. After some interior decorating (she installs the flooring), she lays her eggs and broods the chicks.

THE HANDYMAN CAN

What female black-headed weaver can resist a sweetly singing male, flapping his wings as he displays at his expertly crafted nest?

Lower to the ground, abandoned nests of yellow-crowned bishops are nestled among the bright orange blooms of lion’s tail shrubs. Males made those nests, too. When in breeding plumage, a bright yellow and black male’s courtship involves a behavior that Anne described as his “bumblebee” display. “A male yellow-crowned bishop courts a female by puffing up all his feathers,” Dave said. “He does it when a female looks into his nest, and he does it in flight, in midair.”

OPEN WIDE

A female yellow-crowned bishop feeds her newly fledged chick.

FOSTER PARENTS

As a pair of red-billed firefinches carry bits of grass to a potential nest site, a female village indigobird observes them intently. Indigobirds, along with the closely related whydahs (finches in the family Viduidae), are all brood parasites, meaning that they lay their eggs in the nest of another, host species—which is always a waxbill (finches in the family Estrildidae). The waxbill host incubates the brood parasite’s eggs and raises the chicks alongside its own.

HOW DO YOU LIKE ME SO FAR?

A red-billed firefinch holds a feather in his bill. Showing it to a female is the first step in forming a pair.

Each species typically lays only in the nest of a specific waxbill host. “Chicks have distinct mouth markings that mimic those of their particular host species,” Dave said. Their begging behavior—an unusual, head-down, neck-twisted-up posture—is the same, too. Parents peering into a nest to feed chicks can’t tell the difference between their own chicks and their “foster chicks.”

I LIKE WHAT I SEE

A pair of red-billed firefinches work on a nest (left). A female village indigobird (a male is shown here at right) will lay eggs only in the nest of the firefinch.

For village indigobirds, the host is always a red-billed firefinch (a type of waxbill). Female—and sometimes male—indigobirds check out the nest when the firefinches flit away. “You generally see nest owners chase other birds away from their nest site,” Anne said. “But the firefinches don’t appear to mind the attentions of the indigobirds.”

LOOK AT ME!

During the breeding season, the long tail feathers of a male pin-tailed whydah help him attract mates. The male at right isn’t waiting for his tail feathers to grow in to practice his flight display.

Africa Rocks is also home to pin-tailed whydahs and their host, common waxbills. You’ll spot long-tailed paradise whydahs, too, but currently their host—the melba finch—isn’t a resident. “Working with brood parasites and their host species is exciting and different for me,” Anne said. “Only about one percent of all bird species are brood parasites—and we have three of them.”

“All whydahs and indigobirds do a flight display during courtship,” Dave said. “They hover above the female and sort of bounce,” while singing. Such displays represent a male bird’s best effort to get the attention of a female. But the song is just as important. Males learn the song of the host species, and a female chooses a mate with a song that matches that of her foster parents. In an aviary, “whydahs and indigobirds can’t reproduce until you introduce their host species,” he said. “And then, the host species has to breed.”

IN FINE FEATHER

A long-tailed paradise whydah shows off the sweep of his impressive tail feathers.

SPECIES SURVIVAL

An addition to providing a unique opportunity for breeding weaver birds and brood parasites, the new aviary provides appropriate space for breeding other resident birds. Several of these species—including golden-breasted starlings—are managed as part of an Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Species Survival Plan. Notoriously difficult to breed, the golden-breasted starlings in the aviary wasted no time building a nest and raising chicks. Dave credits this to the aviary design, which is “much more like their natural savanna habitat.”

A PLAN’S IN PLACE

Species Survival Plans are in place for (clockwise from top left) the snowy-crowned robin-chat, white-headed buffalo weaver, golden-breasted starling, African pygmy goose, and violet-backed starling.

Like the African savanna that inspired it, the Africa Rocks aviary is a busy place. A stroll through the sunny habitat brings you close to bird species singing, scolding, fluttering, flying, foraging, bathing, building nests, and chattering.

OLD WORLD “HUMMINGBIRDS”

While there are no true hummingbirds in Africa (or Asia), sunbirds are sometimes called Old World hummingbirds, because they are nectar specialists. The Zoo is one of the few institutions in the US where sunbirds have bred successfully, and we hope to breed the splendid sunbird, seen here, as well.

“There’s an intimate feel,” Anne said. “You’re in close proximity to the birds. I certainly enjoy it.” She has some advice for visitors: “Give yourself some time. Use all your senses. Listen to the beautiful calls of the birds.” You’ll be surrounded by action, and as Dave said, “There is a lot going on in there.”