BY Eston Ellis

Photography by Ken Bohn

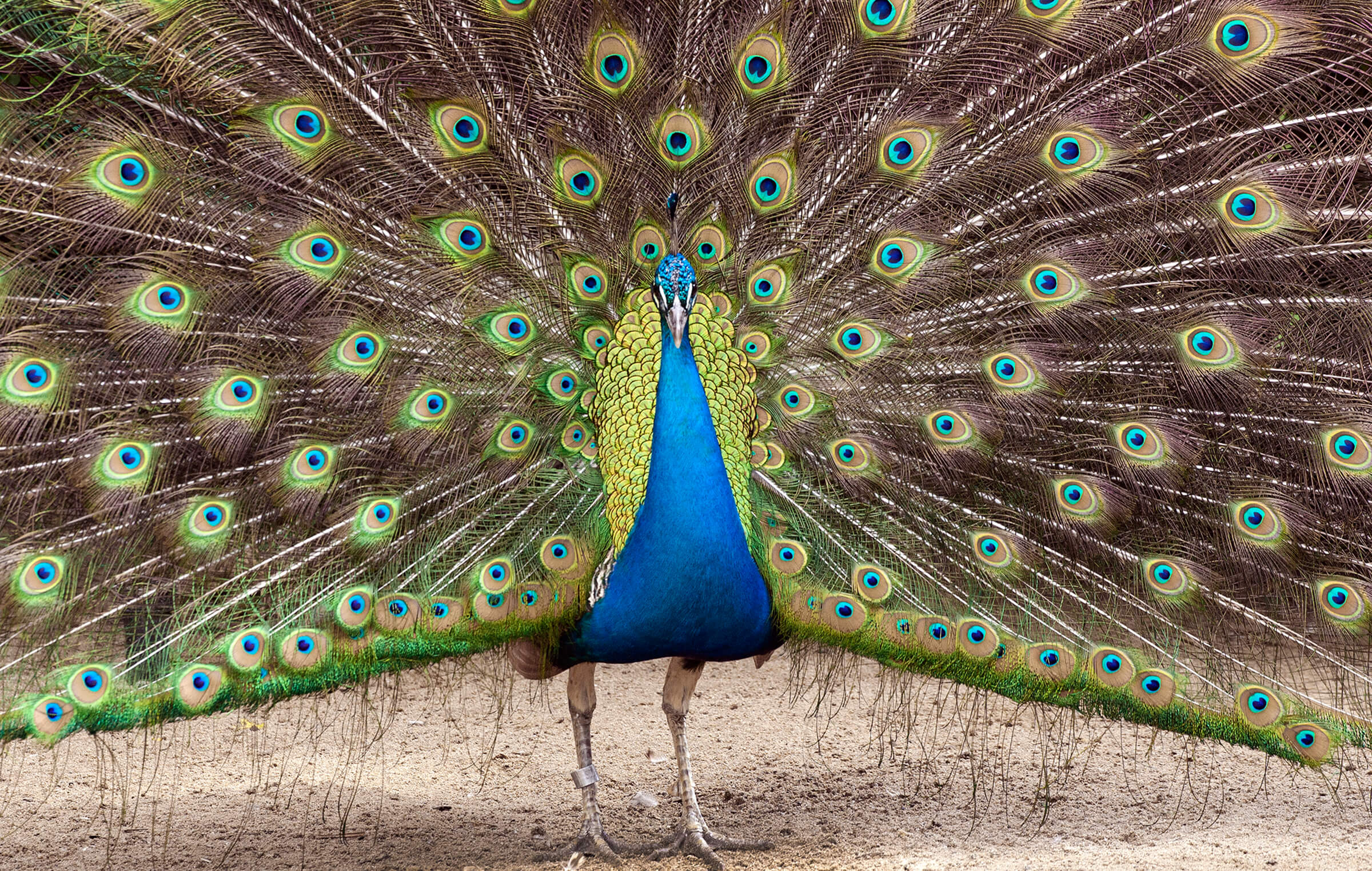

Nothing struts its stuff like a peacock. The male’s dramatic display, raising and shimmying an iridescent, feathery fan of upper tail coverts for females, (or for anyone else strolling by) is a real showstopper. Distinctive Indian peafowl Pavo crisatus—with males referred to as peacocks and females called peahens—first came to the San Diego Zoo in 1924, and it didn’t take long for them to become a favorite among Zoo guests. The current flock of 11 free-roaming birds (6 males and 5 females) make their presence known wherever they go, and they just might be the most photographed species at the Zoo.

“People are just amazed when they see peacocks up close, and I can understand why,” said Dave Rimlinger, head of the Bird department at the San Diego Zoo. “You can’t help but marvel at their beauty.” Both males and females have distinctive fan-shaped crests, somewhat resembling tufts of fuzz on sticks. While Indian peafowl females have brown feathers and just a hint of color on their necks, the males are dazzling, with deep blue and green coloration.

LONG TRAIN

While most people are familiar with the image of a peacock in full display (as at top), that’s not their usual look. More often, their colorful covert feathers are relaxed, draping down from the peacock’s back like the train of a wedding gown.

A train of long feathers—the peacock’s tail coverts—cover shorter, stiffer feathers at the base of the tail that are used to raise the coverts when it’s time for the peacock to “make a statement.” Most of the time, the colorful coverts drape from the peacock’s back to the ground, like the train of formal gown. But when a male raises his train to court a peahen or show dominance to another peacock, that showy, fan-shaped display of long feathers—studded with eye-shaped spots, called ocelli—can be up to seven feet wide.

If, for some reason, a peacock doesn’t catch your eye, he will make his presence known in other ways. “You’ll definitely hear them,” Dave said. Peacocks are known for loud, raucous calls that carry for long distances. They sound off early in the day, late in the evening, and nearly all day long when breeding season rolls around.

They’re Back

The loud, proud, and colorful peafowl flock has returned to the Zoo, after a two-year hiatus. They had been moved to an off-view area to keep them safe after a case of virulent Newcastle disease (VND) was discovered in Southern California in 2018. This contagious disease can affect both domestic poultry and wild birds in the order Galliformes (including peafowl and pheasants), and it can be spread from one area to another on people’s shoes, if they have been in an area where infected birds live—including backyards with chickens. Fortunately, new cases have not occurred for several months, and the VND quarantine was lifted in June of this year, allowing peafowl to once again roam freely throughout the Zoo.

They may be better known for their strutting, but peafowl can fly, and they are among the largest birds that can do so. But they rarely fly long distances—mostly just from the ground to a high tree branch at night and back to the ground again in the morning. While the Zoo’s peafowl wander throughout the Zoo during the day and roost in the trees at night, instances of them venturing off Zoo grounds are extremely rare. While the Zoo occasionally gets a call reporting a peacock on the loose, the bird in question usually turns out to be a non-Zoo bird from a San Diego County backyard or farm, Dave said.

LIVING COLOR

When a peacock raises its feathery fan of upper tail coverts to impress a female or show dominance to another male, that colorful fan-shaped display can be up to seven feet wide.

Peafowl are omnivores, foraging on the ground throughout the day and eating what they find, including fruit, vegetation, grain, insects, and small reptiles or mammals. At the Zoo, peafowl are fed a commercial pheasant pellet, chopped greens, and mealworms, in addition to food they find on their own.

“Our wildlife care specialists know the territories of these guys, and where they hang out,” Dave said. At the Zoo, as in their native range, each male stakes out a small, exclusive territory of his own and chases other males out. However, those small territories within the Zoo are very near each other, allowing each male to hear the other peacocks, and they all know exactly where those other males are.

“One interesting thing about peafowl is how territorial the males are,” Dave said. “If you visit the Zoo often, you might see a peacock in the same general area—such as near the flamingos—again and again. That’s his territory, and he defends it.” He may display to show dominance over any other approaching peacock, and he may behave aggressively toward that “invader.”

PEAHENS, PEACOCKS, AND PEACHICKS

Many people refer to all Indian peafowl as “peacocks,” but that word really only describes the male of the species (right). The female (left) is a “peahen” and young peafowl are called “peachicks.”

Life in an Exploded Lek

Peafowl are lek species, in which the males try to outdo each other with impressive courtship displays to attract a female during mating season. In a typical lek, males gather together in a group, with each one trying to interest a female with his own elaborate display. Peacocks, however, display in what is called an “exploded lek,” where the males are not next to each other but are within earshot of each other; they know the other males are nearby and are also displaying for females.

While the purpose of their display efforts is to win over a peahen that enters their territory, they will continue to display even when no females are around. And peacocks aren’t shy about raising their train and quivering their feathers in close proximity to Zoo guests. “It’s very impressive when they display; they are really intent on showing off for the females, and they are not too worried about anybody else watching,” Dave said.

MUTED TONES

Although male Indian peafowl have distinctive bright blue and green coloration, females have mostly brown plumage, which helps them blend in with their surroundings when they are nesting and raising chicks.

As in other lek species, peafowl are polygamous. A male may mate with several females in a season. After mating, the female lays three to eight eggs in a ground nest, incubates the eggs, and raises the chicks.

At the Zoo, females and males are sometimes kept apart during breeding season, in order to maintain a healthy on-grounds population of 10 to 12 birds. “Every few years, females raise chicks on grounds,” Dave said. “But if every female bred, we would triple the population in one year.”

Peacocks and peahens at the Zoo are once again offering guests a lot to see—and hear. “Peacocks are very much a part of the San Diego Zoo experience,” Dave said. “It’s great to have them back.”

EYE-CATCHING PLUMAGE

The peacock’s long coverts—the feathers covering its tail—are studded with colorful, eye-shaped spots called ocelli. When those coverts are raised in a courtship or dominance display, the “eyes” are everywhere, making the peacock all but impossible to ignore.

Stable and Endangered

Indian peafowl live in forest, grassland, and scrubland habitats throughout their native range, which includes India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. It is the national bird of India—and in some parts of its native range, the species is considered sacred. Because of their beauty, Indian peafowl have been sought after for centuries—and as a result, they have been brought to many other nations. Introduced populations exist worldwide, including in the US, Australia, New Zealand, and the Bahamas.

While Indian peafowl populations are considered stable, with more than 100,000 of them living worldwide, a second peafowl species—green peafowl Pavo muticus—is listed as Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species. Native to China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Malaysia, green peafowl are currently threatened by habitat loss and deterioration, hunting and egg collection by humans, capture for the pet trade, and conflict with farmers.

Fewer than 20,000 mature green peafowl are believed to exist today in their native habitats, “but there have been some discussions about releasing this species into the wild,” Dave said. In addition, this species is now protected by law in China, and public awareness campaigns have been launched to prevent poisonings in agricultural areas.