In 1982, there were only 22 California condors left in the world—the last of their species. To some, the situation seemed hopeless. But thanks to dedicated wildlife specialists at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, there are now more than 500 of the iconic vultures, and more than 300 of them soar over California and nearby states. Here is the story of one of those birds.

BY Donna Parham

Photography by Ken Bohn, SDZG

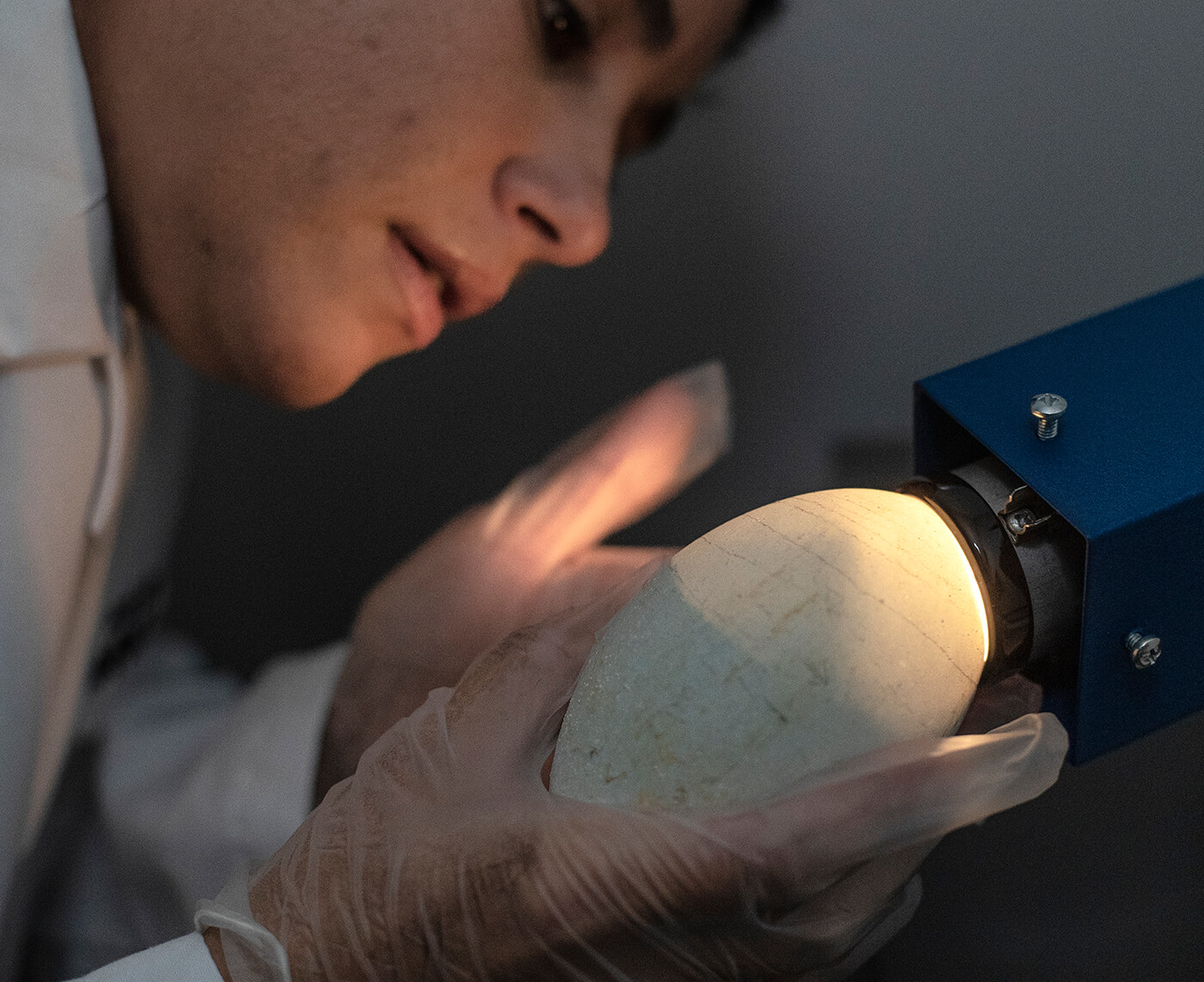

YOU IN THERE?

Holding a fertilized egg against a bright light in a darkened room lets wildlife care specialists see the shadow of the chick inside and make sure it is developing properly. The procedure is called “candling,” and it alerted Safari Park condor care specialists that this chick was upside down.

At the Safari Park, eight breeding pairs of California condors Gymnogyps californianus live in “condorminiums”—the first breeding facility constructed for this species. A female condor typically lays just one precious egg each year. Aviculturists replace it with a wooden replica, placing the real thing in an incubator that maintains just-right temperature and humidity. If all appears well when the chick inside is fully developed, they make the reverse swap, returning the egg to its parents before it hatches.

But inside one of the 2019 eggs, the chick was upside down. “While this is not usually a lethal malposition, we decided not to put the egg back under her parents, just in case the chick were to need help in hatching,” explains Ron Webb, senior wildlife care specialist at the Safari Park. It was a good call. When the chick pipped, it became stuck to the egg membranes in places. With expert assistance, a female chick—given the name Xanan (pronounced HAH-nen)—hatched about 72 hours later. “She was a strong chick, and everything looked great,” Ron says.

XANAN ARRIVES

Xanan hatched on March 21, 2019, approximately 72 hours after she pipped. In spite of the gentle assistance of wildlife care specialists, hatching is an exhausting process for a chick!

Xanan was one of two chicks last year to be hand-reared—although that “hand” was inside a condor puppet, to ensure that the chicks wouldn’t become imprinted on humans. “We try to have parents raise their own chicks, and for the most part, they are successful,” says Ron. When they’re not, “The puppet feeds the chick, and treats it just like parent birds would, so that the chick learns proper condor behavior.” Little Xanan hit all the condor chick milestones: nibbling and nuzzling the condor puppet, exploring her “nest,” and picking up items on her own. “Although it can be a lot of work, it is really fun to watch these little fuzzballs grow,” says Ron. “We can really watch their personalities develop.”

ARE YOU MY MOTHER?

Staying out of sight, Ron and other condor care specialists fed and cared for Xanan using a custom-made puppet that looks—and acts—like a condor parent.

When Xanan was 30 days old, it was time for her first health exam, something she wasn’t enthusiastic about. “She was nervous and defensive when she saw people for the first time—which is actually a good thing,” says Ron. “We want young condors to be wary of humans. Condors that show an affinity for humans seldom survive in the wild.” Veterinary staff were able to do a quick health assessment, checking her eyes, nostrils, beak, feet, legs, wings, and abdomen. They weighed her, took a blood sample from her leg, and vaccinated her for West Nile virus. Finally, they injected a microchip for identification—the same kind you can get for your dog or cat. The whole exam took approximately 10 minutes.

WELL BABY EXAMS

Xanan’s 30-day (left) and 75-day (right) health exams showed her to be developing normally into a healthy juvenile condor. Covering her eyes in a soft cloth helped calm and settle the chick.

Click here to follow condors released in California and learn the history of each bird. When she is released at Pinnacles National Park later in the year, Xanan will be wearing tan-colored wing tag 61.

Click here to follow condors released in California and learn the history of each bird. When she is released at Pinnacles National Park later in the year, Xanan will be wearing tan-colored wing tag 61.

A condor chick reaches another big milestone at about five months old: it’s able to fly, and ready to leave the nest. At this point, Xanan was ready for the next step. “Condors are a social species, and a major part of their rearing is their socialization,” says Ron. Because each condor pair raises just one chick at a time, socialization is something that happens after a chick leaves the nest. So upon fledging, all nine 2019 chicks moved to a remote socialization habitat, with places for perching and roosting, pools for drinking and bathing, and ground-level perches and boulders to hop around on. For the first time, the fledglings, including Xanan, were meeting birds other than their parents.

The youngsters learned important skills and behaviors from a mentor, a 17-year-old female condor named Ojja. “Like us, condors need to learn the rules of how to interact in a group,” says Ron. “The young condors need to learn how to interact with dominant—and sometimes pushy—birds in order to be successful in the wild.” The socialization period for juvenile condors lasts about a year. “They take turns pushing each other around and perching in different areas,” Ron says. “They decide who they want to perch with, and who they want to stay away from—and that’s the whole point of socializing them together after they leave the nest. They really get to know each other.”

CONDOR MIXER

In the socialization pen, condors spend nearly a year getting to know each other. They can perch and roost on oak branches, and drink and bathe in two pools. Ground level perches and boulders give them places to hop around. During this period, the birds are isolated from humans except for during medical procedures.

Just as importantly, during this socialization period, the birds are isolated from all human activity. Their food enters through a chute in the wall; the pools are drained and rinsed from the outside. “The only time the birds see us is during a medical procedure: affixing wing-tags, pre-shipment examinations, or West Nile Virus inoculations—not exactly enjoyable experiences for the young condors,” says Ron. “We are hoping to foster behaviors that wild condors would have—avoiding human activity and hazardous situations. The longer we can keep them here with a mentor, without exposing them to people, the better they do post-release.”

NUMBER TAN-61

Each condor that’s released gets a wing tag. Xanan’s studbook number is 961. The first numeral is denoted by tag color—in Xanan’s case, a tan tag indicates that the first numeral is a 9.

It’s so important, in fact, birds are released with at least one other member of their cohort. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) coordinates the California Condor Recovery Program, and they determine where birds are released. There are three release sites in California, one in Arizona, and one in Baja California, Mexico. USFWS biologists selected Xanan for release at Pinnacles National Park, where the National Park Service (NPS) condor biologists took over.

THE NEXT STEP

Ron assists in transporting Xanan to her pre-release habitat, in a remote area of Pinnacles National Park.

Ron accompanied Xanan and her cohort to Pinnacles, ushering them into the pre-release habitat, where they are somewhat protected as they grow accustomed to their new surroundings. Free-flying birds, including older condors and other local species such as golden eagles, “hang out outside the enclosure and check out the new birds,” says Ron. “This way, the new condors are exposed to resident birds gradually.”

MEETING THE NEIGHBORS

Free-flying condors and other birds stop by to check out the new kids. The juveniles have a chance to get comfortable with their new surroundings and the local birds before they are released.

Xanan spent several weeks in the pre-release habitat before NPS biologists opened the door to allow her access to the greater environment, the second week of November. She was released with a male condor named Kawkikat. (The other seven birds she was socialized with were released at a site in San Simeon, by the Ventana Wildlife Society. There is a very good chance that they will all end up finding each other once they have been released.) Sometimes the birds are hesitant, but not Xanan! She hopped out, spread her wings, and took off. NPS biologists report that she is thriving.

ON HER OWN (SORT OF)

Xanan now soars the skies of California. Her cohort of nine birds offers social support, and USFWS biologists continue to monitor her. (Photo by: National Park Service Photo/Gavin Emmons)

Ron says that even though he’s gotten to know the juvenile birds, he’s always excited for their release. Still, he warns, “There is higher mortality in the wild than in zoos, so there’s always a chance that they’re not going to make it.” Ironically, for a bird that can eat toxic bacteria and is known for cleaning up the environment, one of the biggest obstacles they face is poisoning—lead poisoning.

CONDORS OVER CALIFORNIA

Ron says he always wanted to be an animal care specialist at a zoo. “Working in a zoo is fun and rewarding, and I especially love working with condors, because they are a native species,” he says. “People sometimes forget that we have wildlife here in the US that needs our help, too.”

California’s Assembly Bill 711 requires the use of nonlead ammunition for animal hunting in California, which prevents lead poisoning when condors and other scavengers eat carcasses and remains. Many conscientious target shooters and hunters outside of California have also made the switch to copper bullets, which curl up upon impact rather than shattering and scattering, so they do not poison the meat.

A GROWING FLOCK

With many obstacles to their future removed, condors are repopulating their native range. Juveniles have a dark gray head and neck. By the beginning of its third year, a condor’s neck and head colors begin to develop, and by the time it is an adult, the entire head is yellow, orange, red, or pink.

“With bald eagles, peregrine falcons, and brown pelicans, their big obstacle was DDT, and after we removed that speed bump, all three species were eventually taken off the Endangered Species List,” says Ron. “So when we do whatever it is we want to do out there—whether it’s hunting, or pest control, or anything else—we need to make sure it’s sustainable, so that it doesn’t interfere with what we want to do, or with wildlife.” He acknowledges that conservation problems aren’t always easy to solve. “Conservation isn’t just biology,” he says. “It’s politics, and sociology, and economics—so getting folks to switch to lead-free ammunition is a big step. Once we make that switch, food for condors will be safer.”

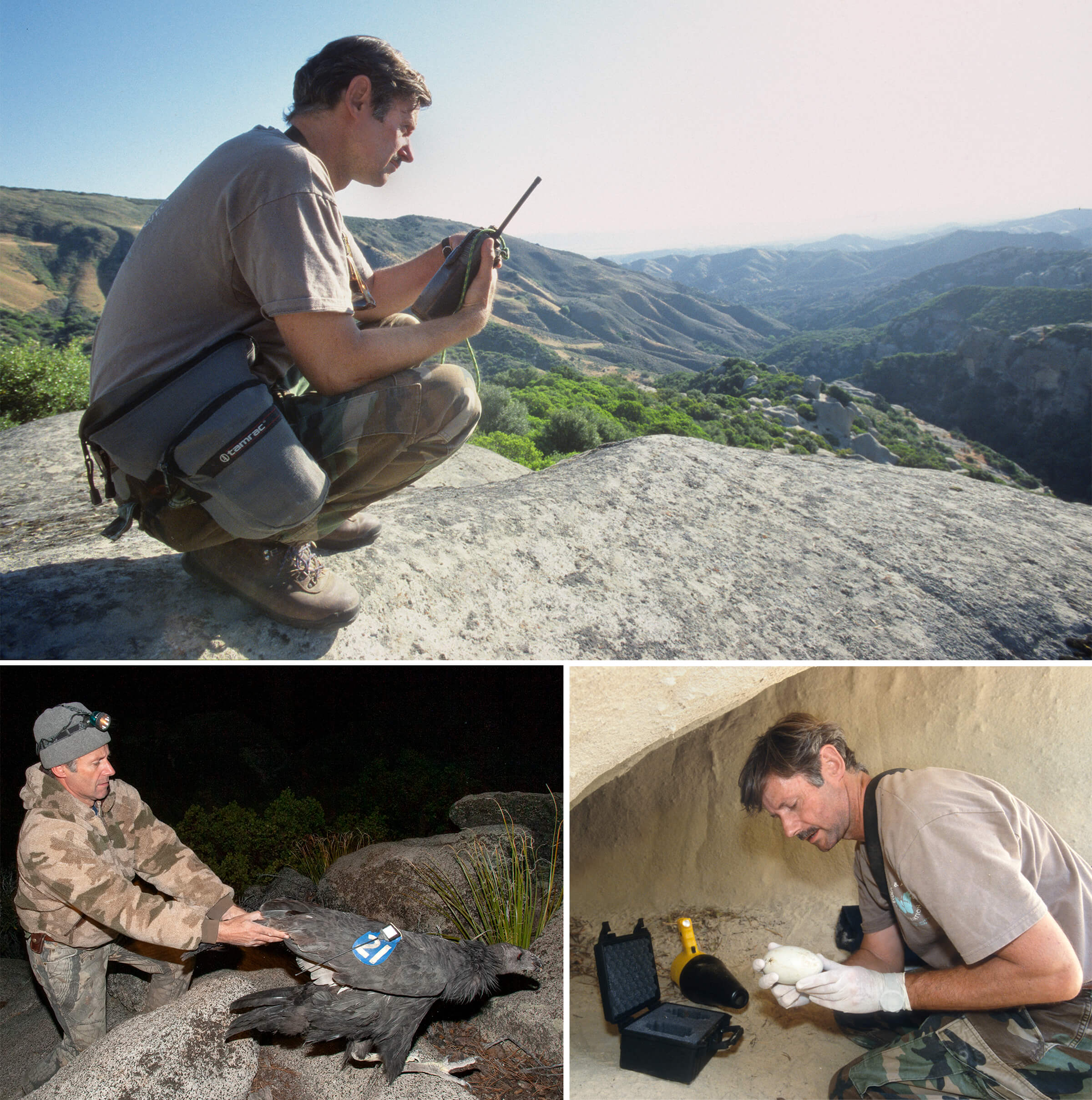

A FRIEND TO CONDORS, AND TO US

A global California condor expert and an enthusiastic field biologist, Mike Wallace devoted much of his life to breeding and reintroducing California condors.

Mike Wallace: His soul now flies with condors

Chumash people believe that when a person dies, a condor carries their soul to heaven. If there ever was a person who deserved this honored flight, it was Dr. Mike Wallace. Mike gave his all for California condors. Much of his life was dedicated to recovering this endangered and iconic bird. You hear the phrase, “dedicated to a cause” often, but that does not do justice to Mike’s passion for condors. Always an avid devotee of all birds, his dedication to condors began with his Ph.D. dissertation research on the Andean condor in the early 1980s. He focused his passion on breeding and reintroducing California condors for the rest of his career, first at the Los Angeles Zoo, then at San Diego Zoo Global, serving as the California condor coordinator for the Association of Zoos and Aquariums and the Condor Recovery Team leader for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

We are indebted to Mike for his many accomplishments, which were instrumental in developing our successful legacy for this species. It was his dream to restore California condors to Baja California, Mexico. After years of planning, he spearheaded the first reintroduction of condors to Mexico, and as a result, 39 condors are currently flying free over the forests and deserts of the San Pedro Martir mountains. His legacy continues to live on in the condors soaring over Mexico, and in the hearts and minds of all the people he touched. We will remember him as a global expert of California condors, but also as an enthusiastic field biologist, and a kind, gentle, and patient individual.

After suffering a series of strokes, Mike passed peacefully on October 13, 2020. He will be greatly missed by his daughter, Dayna, along with his family, friends and colleagues.