It’s a familiar story: flames rage through Southern California landscapes. Do these burns benefit ecosystems, or do they damage habitats and reduce biodiversity?

BY Donna Parham

Photography by Tammy Spratt

As it turns out, one size (or type) of fire does not fit all plant communities. While Smokey Bear encourages us to prevent forest fires, some plants actually require fire for seed germination. Forest managers may allow some fires in uninhabited areas to burn, as fire ecologists tell us that low intensity fires remove forest underbrush (fire fuel), and can thwart larger, more destructive fires. The dominant landscape in Southern California, however, is not forest. Here, chaparral and sage scrub cover almost two million acres of National Forest System land.

SAGE SCRUB—NOT FOREST

The dominant vegetation community in Southern California is chaparral and sage scrub.

FRIENDLY FIRE

Some chaparral plants are adapted for surviving fire. Joe Davitt, plant conservation research associate for San Diego Zoo Global (SDZG), explains: “In some plants, the heat of the fire causes a seed coat to split, and that allows water to get to the embryo.” The tightly sealed cones of the Tecate cypress Callitropsis forbsii, a designated California Rare Plant and a conservation priority species for SDZG, only open after fire. “Fire breaks the resinous seal around the little sections of the cone, and after the fire, they pop open, and seeds come out,” says Joe.

The seeds of some species are stimulated by smoke and char. “These seeds are triggered to germinate by chemicals in smoke—not the physical heat from the fire,” says Joe. “Research has shown that many chaparral species respond positively when germinated with smoke water, and some are entirely dependent, germinating almost exclusively in the presence of smoke chemicals.” Known as a “fire-follower,” whispering bells Emmenanthe penduliflora is a well-known example. “Of course, these species don’t actually ‘follow’ a fire,” says Joe. “Their seeds lie dormant in the soil until the chemical cues after a fire trigger them to germinate.”

FIRE FOLLOWER

Known as a “fire-follower,” whispering bells seeds lie dormant in the soil until after a fire. Researchers at the Native Seed Bank showed that chemicals in smoke water serve as the germination trigger. (Photo by Andrei Stanescu/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

And some scorched plants create a clone of themselves, thanks to a root system that is also an underground energy source, called a burl. “If the above-ground plant burns away, the plant sprouts from this underground storage tissue,” says Joe. “When water hits it, it can grow very quickly.” He cites examples of chaparral and sage scrub plants like laurel sumac Malosma laurina, chamise Adenostoma fasciculatum, and many of the local manzanitas Arctostaphylos.

ENERGY STORAGE

The underground root tissue of some chaparral plants stores energy, allowing plants “destroyed” by fire to resprout—as long as fire isn’t too frequent. A few examples (left to right): laurel sumac, chamise, and bigberry manzanita.

IT’S COMPLICATED

So, is fire good for Southern California sage scrub and chaparral? Not exactly. “Fire is complicated,” says Charlie de la Rosa, Natural Lands Manager for SDZG. Charlie oversees recovery and restoration efforts, biodiversity monitoring activities, and research on the 800-acre Biodiversity Reserve adjacent to the Safari Park. “Fires can actually release a lot of nutrients into the soil, and they clear away competitors for light, which makes it a pretty great place for seeds to germinate.” In fact, it doesn’t take long for seedlings to cover the scorched earth. “A large fire shakes everything up,” says Joe. “Some individuals die, new plants grow, and genes are added.”

CONSERVATION IN ACTION

The SDZG Natural Lands Program is managing invasive plants on 30 acres of sensitive habitat in the Biodiversity Reserve adjacent to the Safari Park. Researchers like Charlie de la Rosa (shown) are studying the effects of invasive species and best practices for managing them, and sharing their results with our conservation partners throughout the region.

So far, sounds good. But both researchers are quick to add a critical caveat. “Chaparral and sage scrub plants are adapted for fire, but on a very long-term scale,” says Charlie. “We’re now seeing these big fires come through at higher rates, more like every 10 to 20 years, instead of every 100 years,” says Joe. “That’s the big threat—a species doesn’t have time to recover between fires.” For thousands of years, lightning strikes were just about the only cause of fire in these areas—something that happens only every 30 to 100 years. Nearly all the recent fires in Southern California are now started in some connection to humans. “The most common source is a power line-related issue,” says Charlie. “Then there are the incidental fires that start from a hot catalytic converter, a cigarette, or a campfire.”

FIRE FUEL

Sage scrub habitat evolved to burn when lightning strikes—something that happens infrequently in the Southern California dry season.

FIRE FREQUENCY

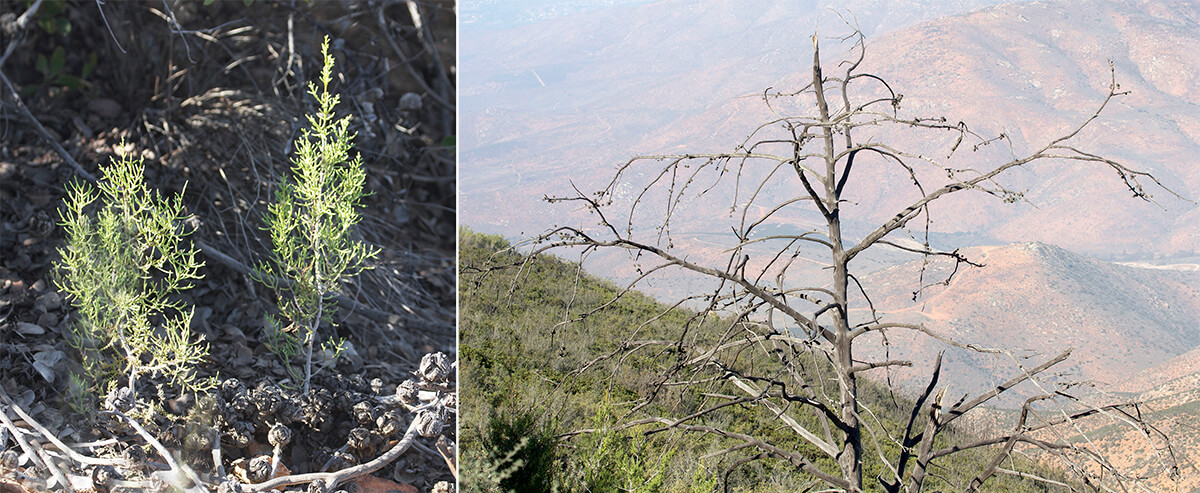

Fire frequency matters. Just look at what could happen to the imperiled Tecate cypress: “If a fire passes through, it would burn adult trees and open their cones,” says Joe. “The seeds drop to the ground and germinate, but they need another 15 to 20 years before they are producing new cones. If another fire comes through and burns young trees before they have the ability to produce cones and seeds, then you’re potentially wiping out the entire population.” That’s exactly what happened when wildfires blazed through San Diego County in 2003 and again in 2007. Tecate cypress seedlings that sprouted after the 2003 fire burned in the 2007 fire—before they were large enough to produce cones of their own.

SOME LIKE IT HOT

But only when they’re old enough to reproduce. For a Tecate cypress, that’s about 15 to 20 years. Fires that roar through a stand more frequently have the potential to destroy the entire population.

INVASION

Our native plants aren’t the only ones adapted for surviving fire. In Mediterranean zones around the world, there are plants that are similarly adapted—and some of them have become invasive species that threaten our native landscapes. Native to the Mediterranean climate of South Africa, stinknet Oncosiphon piluliferum is quickly spreading through Southern California. Part of the secret to its success is adaptation to fire. Research at SDZG showed that significantly more stinknet seeds germinate in response to chemicals in smoke water. “These fast-growing, invasive annuals can take over areas before native seeds and plants recover,” says Charlie. Many of these invasive plants, particularly non-native grasses and other fast-growing weeds, also contribute to fire frequency. “They create biofuel, and their thatch is like tinder,” says Joe.

MEET THE ELEPHANT

When it comes to fire ecology, “Global climate change is definitely the elephant in the room,” says Charlie. As global temperatures increase, Southern California weather conditions have become more unstable. “The main change that relates to fire is increased periods of drought,” he says.

Charlie explains why chaparral and sage scrub are especially vulnerable to drought. “Chaparral and sage scrub plants are adapted to a short wet season—when they essentially get all their nutrients and all their moisture—and a long dry season. They invest their growing, fruit, and seed production into the short, wet periods of time, and then they have to hold on to life with root resources during the dry period,” he says. “If you have dry period after dry period after dry period, chained together, then those resources are not going to be sufficient. If you add in a disturbance like fire, you can end up with whole vegetation communities that change, because those plants just can’t hold on anymore.”

KEEPING SEEDS SAFE

In the fight to preserve our natural lands, one vital resource is the SDZG Native Seed Bank, curated by the SDZG Plant Conservation team. The bank safely stores the seeds of more than 440 native species, providing insurance against catastrophic loss. Joe and the plant conservation team also research dormancy-breaking protocols that ensure the seeds can be grown when needed. “For species that require the heat of a fire to germinate, we might put them in hot water, or in an oven,” Joe says. For seeds that respond to chemical cues in smoke, “We run water through material that’s been burned. Soaking seeds in the smoke water, even at room temperature, is enough to trigger germination.”

Experts have used seeds from the bank to propagate plants to improve the habitat of coastal cactus wrens and other sage scrub-dependent plants and animals. And they’ve propagated Tecate cypress from seeds, establishing a field gene bank to provide large amounts of seeds should one of the three remaining populations in the county be consumed by fire.

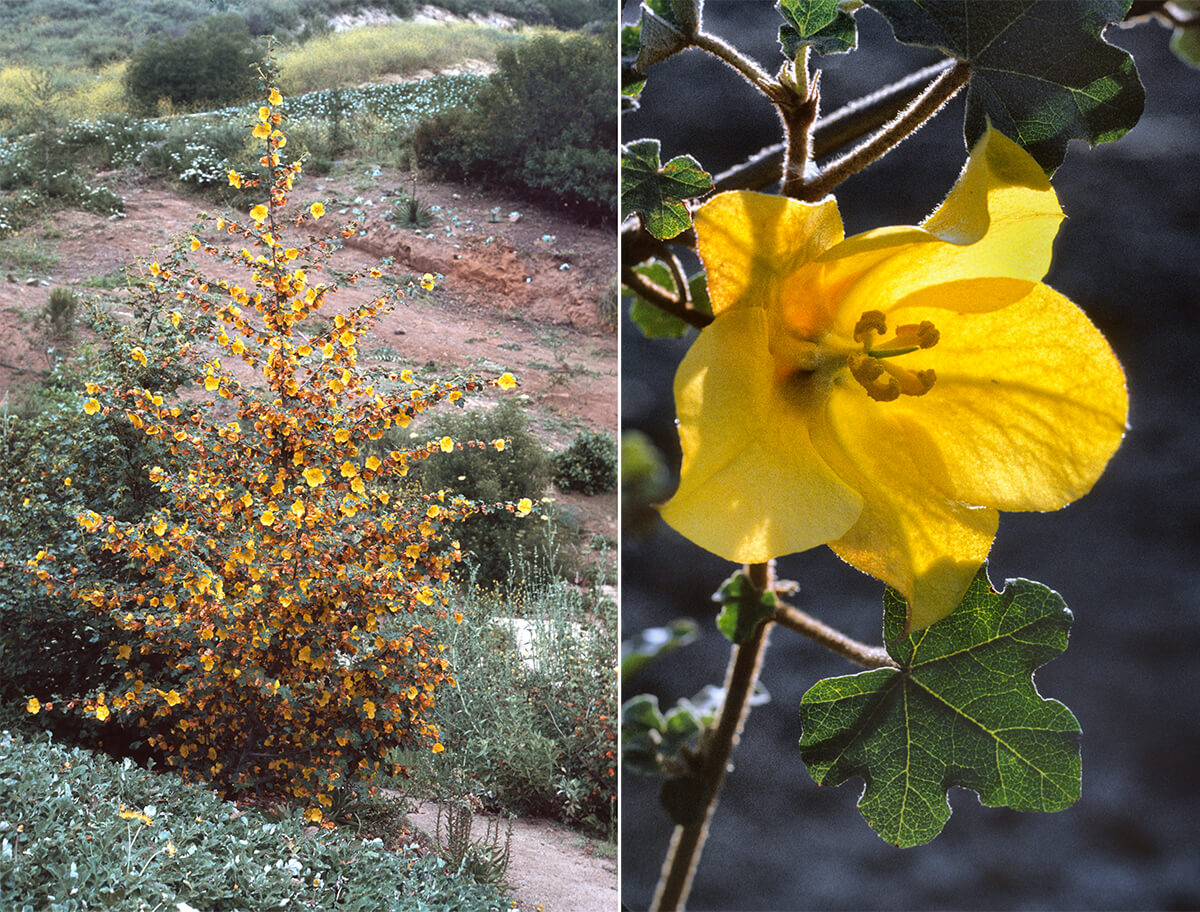

MEXICAN FLANNELBUSH

The seeds of Mexican flannelbush Fremontodendron mexicana, a federally endangered species and a priority conservation species for SDZG, have tough, hard seed coats. SDZG researchers have been able to trigger germination by sanding the seed coats or by hot-water treatment.

MAKING LEMONADE

“Many coastal sage and chaparral plant species have evolved ways to make the best of a very bad situation,” says Charlie. “If catastrophe strikes, these species can survive by quickly germinating or resprouting. That doesn’t necessarily mean fire is good for them, but rather that they can make lemonade from lemons by tolerating and adapting to fire—up to a point.” Ongoing SDZG research addresses the effects of fire on our native habitats, and our Natural Lands Program and Plant Conservation teams are dedicated to maintaining native habitats in the face of too-frequent fires, invasive species, and climate change.