Zoo InternQuest is a seven-week career exploration program for San Diego County high school juniors and seniors. Students have the unique opportunity to meet professionals working for the San Diego Zoo, Safari Park, and Institute for Conservation Research, learn about their jobs, and then blog about their experience online. Follow their adventures here on the Zoo’s website!

Conservation is a fight against the future and the past. As many people know, there are only two northern white rhinos left in the world. Past poaching and habitat loss have caused the northern white rhino to be in the state they are today, but what we do now for this species can also determine its future.

Conservation is a fight against the future and the past. As many people know, there are only two northern white rhinos left in the world. Past poaching and habitat loss have caused the northern white rhino to be in the state they are today, but what we do now for this species can also determine its future.

Dr. Chris Tubbs, a Senior Scientist for the Reproductive Sciences team at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, has been working with the Institute for 11 years to incorporate new technologies into programs working to save endangered species from the brink of extinction. Currently, Dr. Tubbs is working on finding ways to bring back the northern white rhino. Since the only two northern white rhinos left are a mother and a daughter, there is no natural way to bring this species back from extinction. However, in the Frozen Zoo, a collection of stem cells, reproductive tissues and cells, samples from about 10,000 individuals representing 1,000 species are frozen and preserved in massive tanks cooled by liquid nitrogen. In recent years, technology has found ways that could theoretically bring back entire species from these stored samples.

One of the up and coming methods is stem cell technology. This technology allows researchers to synthesize rhino sperm and eggs from genetically ambiguous cells called stem cells. These synthesized sperm and egg cells could then be implanted into a viable surrogate, which in the case of the northern white rhino, would be its close relative, the southern white rhino. In recent months, two of the six female southern white rhino at the Safari Park have been artificially inseminated with southern white rhino sperm, resulting in a successful pregnancy. Scientists hope that one day it will be possible to implant a northern white rhino embryo into a southern white rhino using in vitro fertilization. Although current technologies do not permit such a process to occur yet, there is also concern that any successfully created descendants will lack genetic diversity, making the surviving rhinos genetically similar, and thus making it hard for the species to adapt, evolve, and ultimately survive. Years ago, the revival of the California condor came across similar complications. The California condor was very near extinction, but was successfully brought back from 22 individuals remaining in the wild. In regards to the Rhino Rescue Project, only 12 northern white rhino cell lines are available for use, so researchers can only hope that this revitalization will be successful.

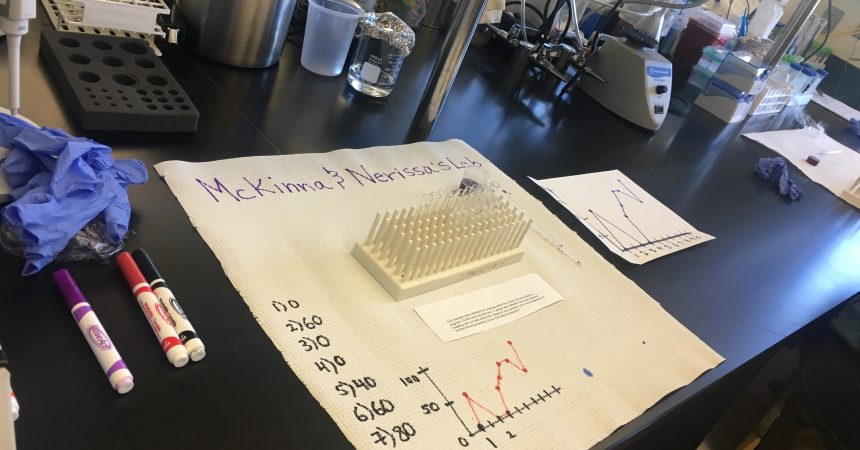

At the current moment, since two southern white rhinos have already undergone successful artificial insemination, researchers are monitoring the rhinos’ pregnancy. Since pregnancies in certain animals may not be physically noticeable until later stages, researchers on Dr. Tubbs’ team must conduct hormone assays, or experimental tests, on the organism’s excretions or bodily tissues. Dr. Tubbs’ and his coworkers usually uses an animal’s urine or feces to conduct these tests because it is much easier to retrieve compared to something more invasive like acquiring a blood sample. In these experiments, data on the amount of progesterone, which is a hormone released when the body is preparing for pregnancy, is recorded and analyzed to determine the best course of action keepers and veterinarians must take to ensure a successful pregnancy.

In the end, conservation isn’t only a fight against the future and the past. Although we might be paying for the consequences of our past actions, we are using samples we once collected from extinct and near extinct species. On the other hand, we may be fighting against time to keep near extinct species such as the northern white rhino from dying off, but we are also working with new technologies that may be able to help us preserve existing species and even bring back extinct ones. That’s why, in reality, conservation is a fight with the future and the past.

Nerissa, Conservation Team

Week Two, Fall Session 2018