Zoo InternQuest is a seven-week career exploration program for San Diego County high school juniors and seniors. Students have the unique opportunity to meet professionals working for the San Diego Zoo, Safari Park, and Institute for Conservation Research, learn about their jobs, and then blog about their experience online. Follow their adventures here on the Zoo’s website!

Have you ever wondered how reproductive physiology relates to conservation? Well, the Reproductive Sciences team at the Institute for Conservation Research is utilizing scientific research to bring many species back from the brink of extinction. While their main project focuses on northern and southern white rhinos, they do a variety of work on many different endangered species. However, their work with rhinos has generated the most attention. Creating new technologies to help artificially inseminate southern white rhinos has allowed Dr. Chris Tubbs, Senior Scientist, and Ms. Rachel Felton, Research Coordinator, the opportunity to contribute in the global efforts to save the northern white rhino. In this photo series, their work will be explained and shown through our inside-look into their lab and the research they conduct everyday.

The Frozen Zoo is known as San Diego Zoo Global’s repository of frozen DNA samples. It holds DNA from over a thousand species, including mammals, birds, and reptiles. The cells are maintained by scientists at the Institute for Conservation Research. More specifically, the Frozen Zoo houses samples of eggs, sperm, tissue, and skin from a multitude of endangered species.

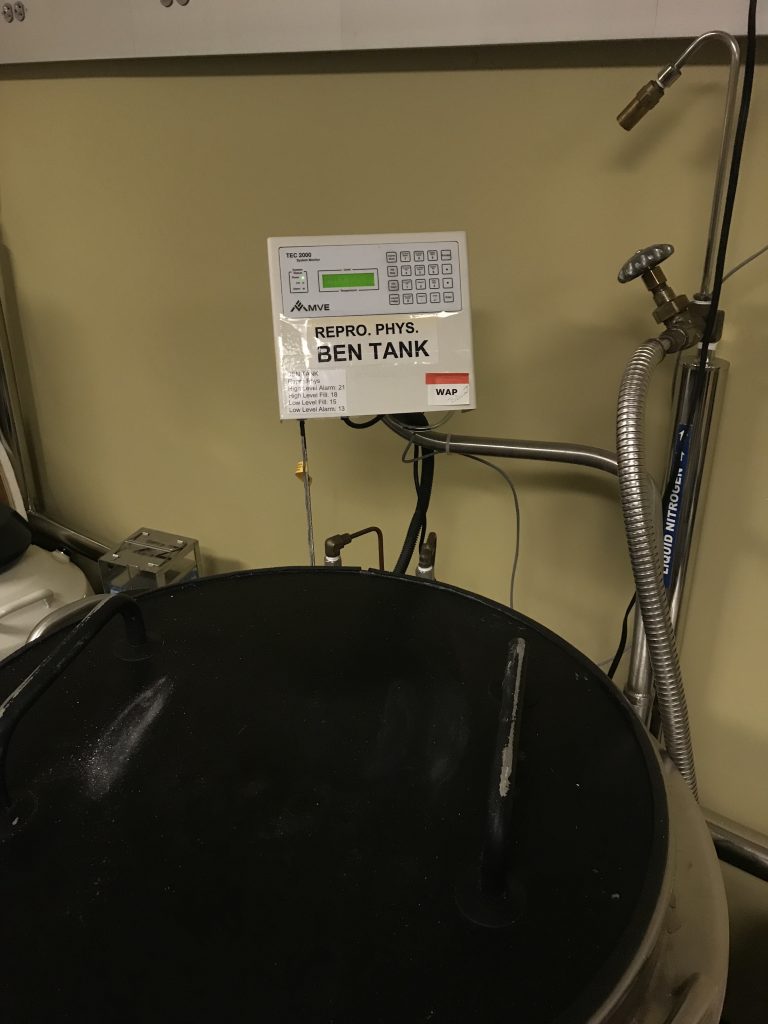

There are around seven tanks similar to the one pictured above in the Frozen Zoo. Collectively, there are around 10,000 individuals represented in each tank. There are cells from extinct species, such as a bird species that was native to Hawaii.

This tank contains samples from many different species. The Reproductive Sciences team is focused on the study of molecular endocrinology in various reproductive systems. More specifically, this means Dr. Tubbs and Ms. Felton examine the hormones related to the reproductive system. One of the hormones Dr. Tubbs mainly works with is progesterone. He explained that this hormone prepares the uterus for pregnancy. High levels of progesterone often indicate an animal may be pregnant, yet many other factors contribute to determining pregnancy.

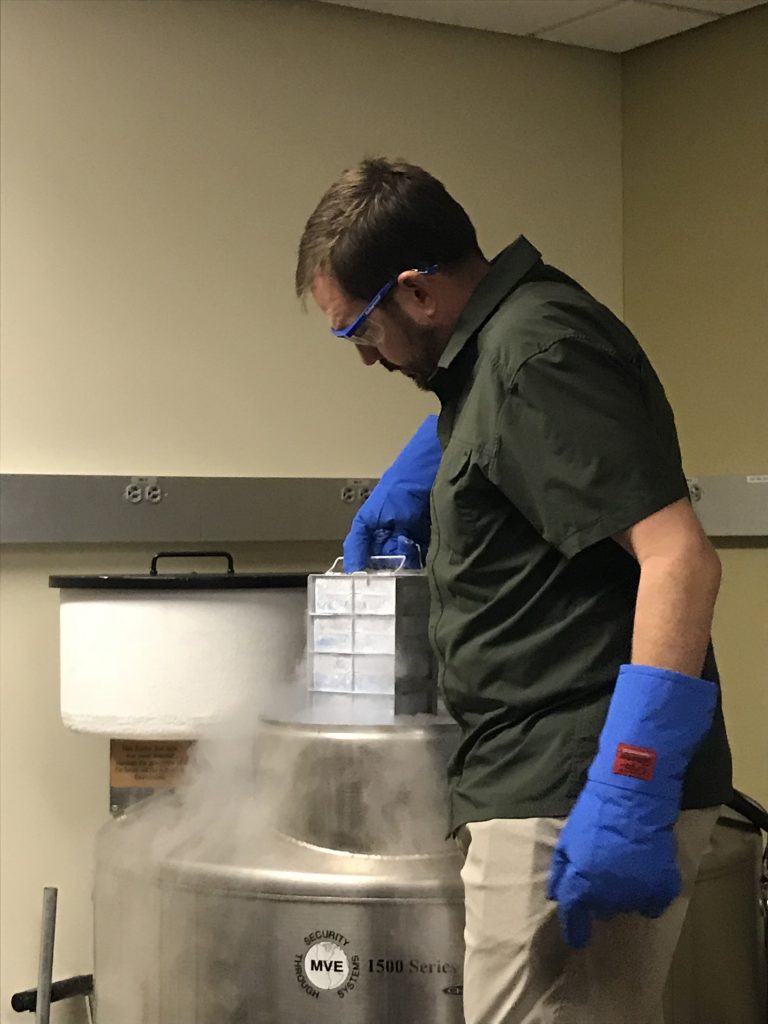

This is a look inside one of the tanks. These racks of genetic information fill up the tanks that are hooked up to liquid nitrogen and kept at a cool -140 degrees Celsius. Liquid nitrogen allows these samples to be properly stored to stay frozen. However, as a precaution, there are duplicates stored at a facility near the San Diego Zoo in case anything happens to the Frozen Zoo at the Institute for Conservation Research.

Next, we made our way to Dr. Tubbs’ lab. There, we were shown the lab’s freezer full of rhino feces, as shown in the photo. In this lab, there are many freezers, desk space to conduct experiments performed by Ms. Felton, and ways to analyze data, typically through a computer. They collect an abundance of rhino feces because it gives them the information they need without drawing blood, which can be invasive. Through the samples of feces, they can monitor the progesterone levels and determine if an animal is pregnant or not.

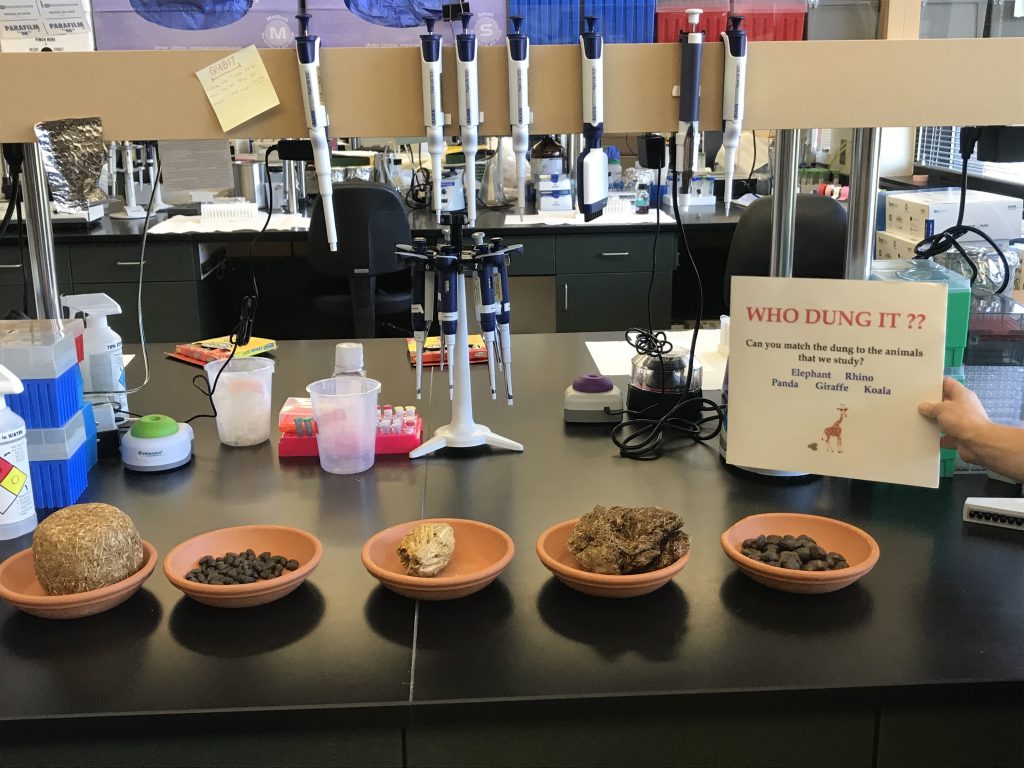

“Who Dung It?” is a game we played to test our knowledge of animal feces. In teams, we had to determine which feces matched to the specific animals. Our options were elephant, rhino, panda, giraffe, and koala. Can you guess what feces belong to what animal? From left to right: elephant, koala, panda, rhino, giraffe.

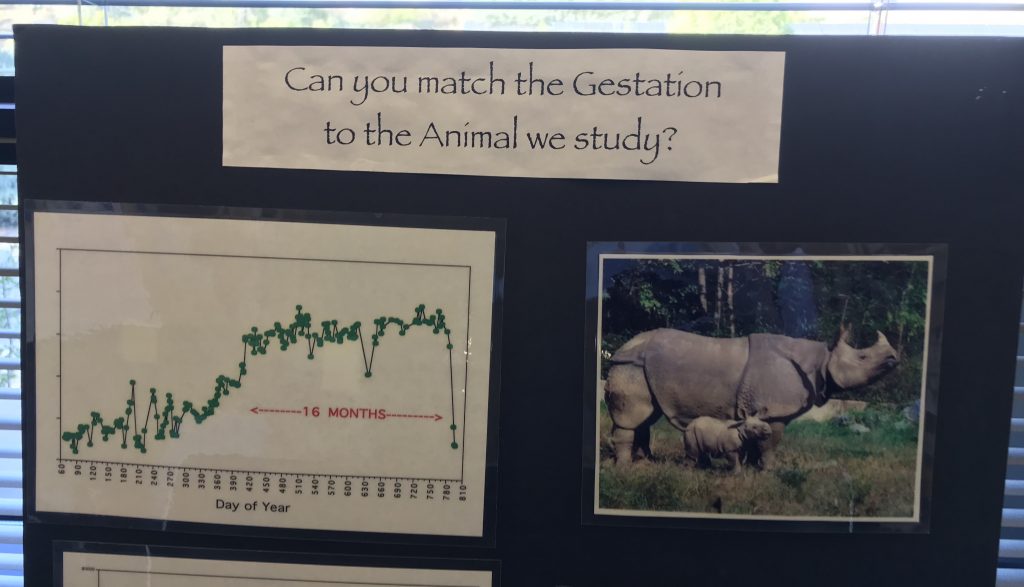

Additionally, we learned about gestation and progesterone levels in different animals. Rhino gestation is around 16 months, and the progesterone levels spike during ovulation and pregnancy. At the end of pregnancy, the levels of progesterone drop very low but it is rare for Dr. Tubbs or Ms. Felton to ever catch that before the baby arrives.

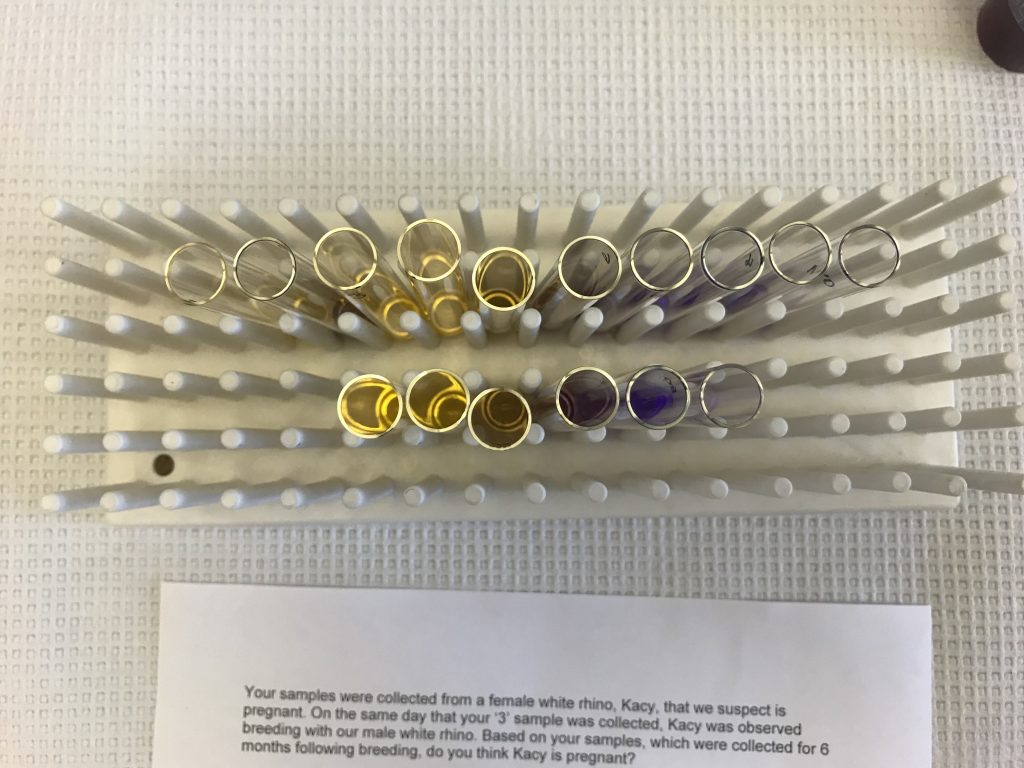

Finally, we divided into pairs and were given a scenario relating to rhino gestation and progesterone levels. Nerissa and I were given the scenario pictured above. Once we were familiar with our specific scenario, we then had to determine unknown levels of progesterone using colored dye while comparing to a series of known levels.

These tubes are filled with the known and unknown levels of progesterone. The left row of samples are still unknown, while the right row shows the known levels.

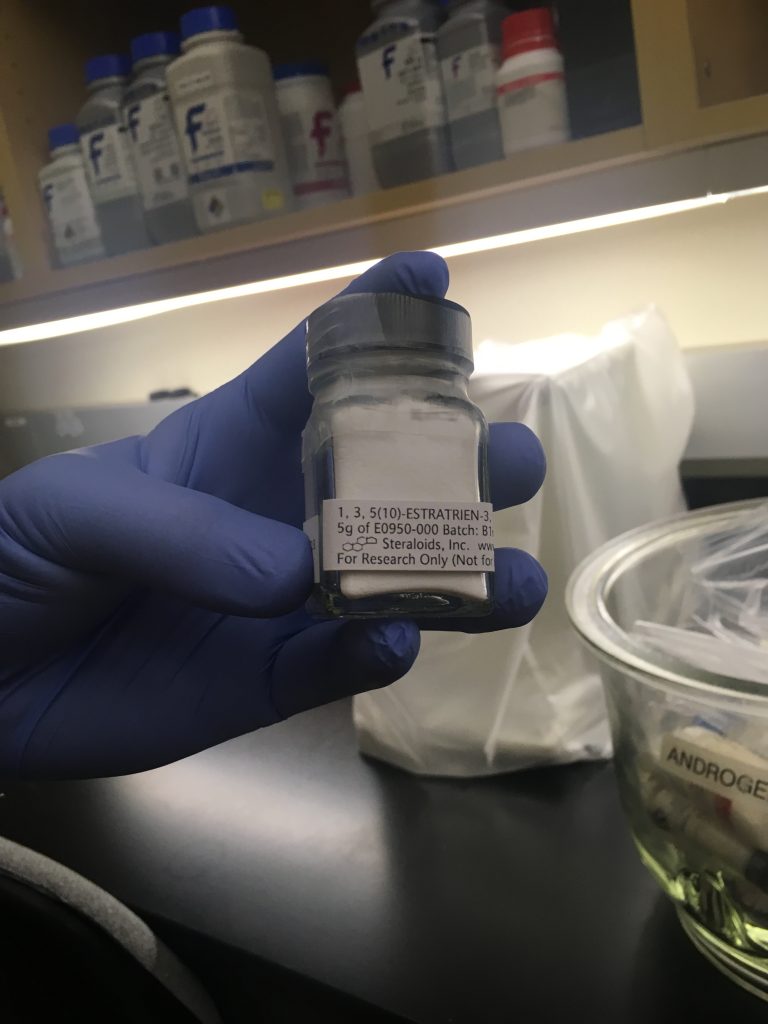

Dr. Tubbs is holding a five-gram bottle of estrogen. By creating known levels of estrogen and progesterone, Dr. Tubbs and his team are able to compare the unknown levels in the samples collected, and ultimately, determine whether or not an animal may be pregnant or ovulating.

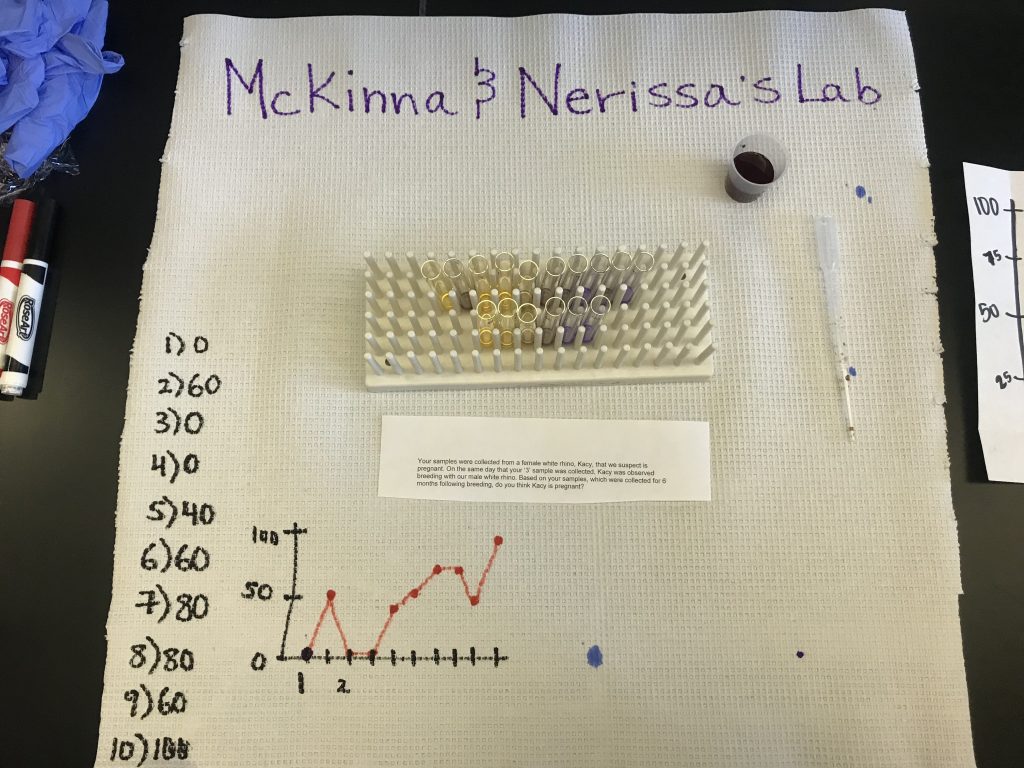

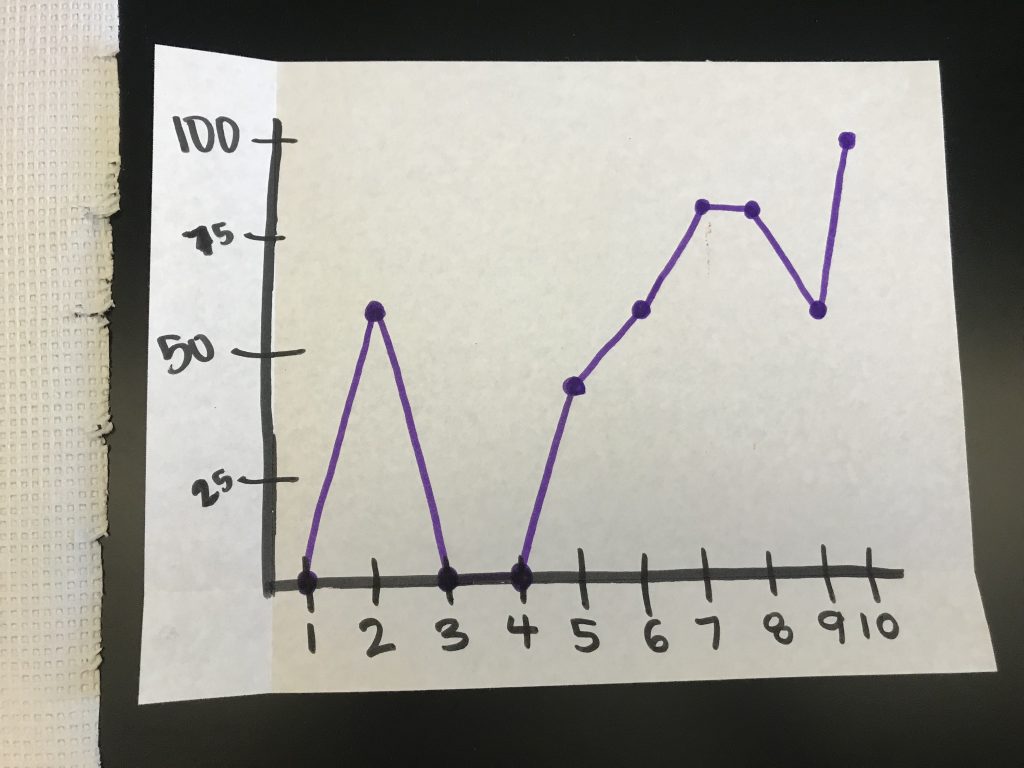

In the photo, we recorded our findings before plotting them onto a graph. The first tube matched with the zero standard, the second tube matched with the 60 standard, and so on. This data set gave us an idea of what our graph would look like in the end.

Lastly, in our graph the spike from the first data point to the third data point shows ovulation. The break after the third point is when breeding occurred, according to our scenario. Then, the levels of progesterone continue to increase and exhibit the first fraction of pregnancy.

Meeting with Dr. Tubbs and Ms. Felton gave us an inside look into the Frozen Zoo and how they are contributing to the conservation efforts of the San Diego Zoo. Rhino gestation is a fascinating topic and intriguing to many, not just the Reproductive Sciences team at the Institute for Conservation Research. I encourage you to keep up with their research and findings, not just on the rhino project, but on any project involving conservation genetics because of their groundbreaking work.

McKinna, Photo Journalist Team

Week Two, Fall Session 2018