BY Karyl Carmignani

Photography by Ken Bohn

Videography by Sharyn Umana-Angers

As the giant orange sun slips behind the horizon in Africa, a big-eared, sharp-clawed, arched creature stands at her burrow entrance, elongated snout twitching. Assured no danger lurks nearby, she heads out at a trot, zigzagging, nose to the ground, listening through the crickets’ jabber for the telltale scratchy sound of termites swarming in column formation. The bowed creature can also sniff out termite mounds, using her claws to handily break into the nest—leaving enough behind so the insects will rebuild. This 140-pound mammal must eat thousands of the tiny insects each night, so aardvarks harvest them where and when they are most concentrated. It is no wonder the aardvark is nocturnal—its primary food source is, too! Despite being the very first word in English dictionaries and a favorite alphabet animal, little is known about the aardvark, which derives its name from the Dutch Afrikaans word for “earth pig.”

The Mysteries of Flora

Throughout their home in sub-Saharan Africa, aardvarks Orycteropus afer (meaning “digging foot”) use their muscled legs and formidable shovel-shaped claws to create burrows up to 10 feet deep, which they use by day. They break into cement-hard termite mounds by night. This unusual animal is committed to “myrmecophagy,” meaning it eats termites and ants almost exclusively. The one culinary exception for the aardvark is the cucurbit Cucumis humifructus, a type of cucumber that grows underground. In South Africa, this plant survives near deserted aardvark burrows, earning it the name “aardvark cucumber.” This melon-like fruit ripens about a foot underground (a strategy called geocarpy), safe from rodents and other seedeaters; its leathery outer rind keeps it from rotting in damp soil. However, germination of its seeds requires sunlight, and that’s where the industrious aardvark plays a crucial role.

WHAT’S FOR SUPPER?

At the Zoo and Safari Park, aardvarks get a special concoction of ground insectivore diet. It looks like peanut butter, but you probably wouldn’t want to put it on your whole grain bread!

Aardvarks excavate the fruit—whether to quench thirst or squelch hunger is debatable—and they excrete the seeds. Though the animals bury their waste (more about that later), it is just a sprinkle of dirt, so the seeds can still get their required sunlight while developing in a heap of nutrient-rich aardvark dung. The cucurbit requires the services of the aardvark to reproduce, growing only where aardvarks are present, and the aardvark is the only creature known to consume this fruit and “replant” its seeds, so they enjoy a mutualistic relationship!

What’s That Smell?

With the stiff tail of a kangaroo, the rounded spine of an elephant, the ears of a donkey, the long, soft, roundish snout of one that smells for living, and sharp toe-claws all its own, it can be difficult to settle on a taxonomic space for this animal. Aardvarks were misclassified with other termite eaters like pangolins and giant anteaters, until anatomical evidence led to a reclassification of the aardvark into its own order, Tubulidentata; its own family, Orycteropodidae; and its lone genus, Orycteropus. The curious aardvark has earned its taxonomic independence! Its peculiar appearance, solo lifestyle, and nighttime habits have kept the aardvark shrouded in mystery. Within the admirable snout, there is a labyrinth of 10 thin bones, the most of any mammal, vastly increasing its keen olfactory sense.

MEALWORMS ARE A FAVORITE MENU ITEM

Aardvarks are keen on using their long, sticky tongue to collect a meal.

Once a termite mound is sniffed out, the aardvark squats in front of it, gives it some scrapes, and rips it open, which brings the insects to the surface. Using its sticky, wormlike tongue, the aardvark takes in the termites, and swallows them. Its strong stomach muscles, which function like a chicken’s gizzard, will grind them up. The aardvark does not completely destroy the termite mound in a single visit, but returns to it successive nights to feed. Which brings us to the aardvark’s fastidious habit of burying its poop. In a two-inch-deep hole, the aardvark deposits its pellets, and flings soil over them, most likely because its waste stinks of ammonia from the defensive repellent contained in all the termite soldiers it consumes.

Keystone Species

Aardvarks dig three types of burrows: the overnight variety, called a “camping hole”; a long, straight tunnel nearly 10 feet deep, sometimes with multiple entrances; and a multichambered burrow ideal for raising a youngster (females typically bear one baby at a time, after a 7-month gestation). If predators like lions or hyenas are threatening the aardvark, it can trot away and dig itself to safety within minutes. Burrows stay a constant 75 degrees Fahrenheit, so the aardvark can do without a “lagging,” or layer of fat under the skin. In chilly winter months, they will leave the burrow earlier to catch the warmth of the sun. An aardvark uses the same den for a period of time, but as the fastest digger in Africa, it’s no great hardship to move on and create another burrow. Other animals quickly move into the vacancies: warthogs and hyenas use them by night, while jackals, ground squirrels, hedgehogs, mongooses, hares, genets, and porcupines move in by day. Lizards, snakes, owls, and bats also benefit from these abandoned homes. The dens also protect animals from brush fires. However, farmers are not so keen on aardvark dens, as they interfere with cultivated land, and livestock can fall into the burrows and get injured.

A Walk on the Wild Side

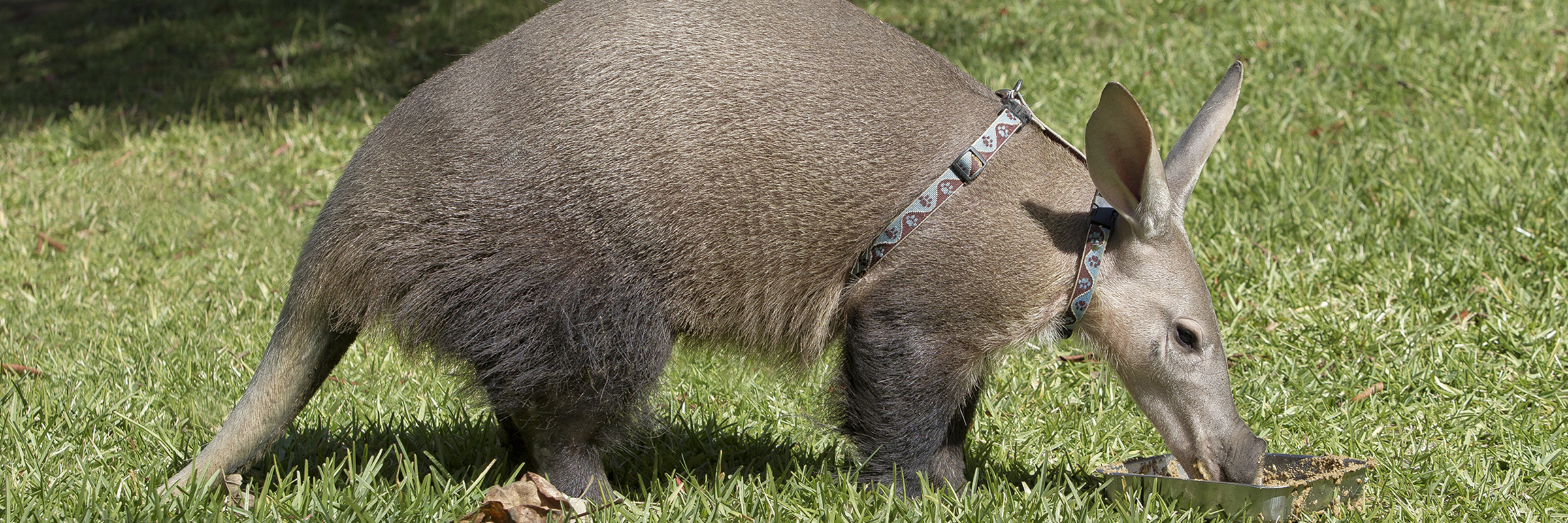

With scarcely over a dozen aardvarks in AZA-accredited US zoos, it is no wonder few people are familiar with them. The Safari Park is home to five-year-old Danny (seen above), who is described as “energetic and inquisitive” by Donna Kent, senior animal trainer. While he enjoys snoozing during the day, Danny seems to understand he has a job to do. Along with Vicki Laurie, senior trainer, the keepers prepare a dish of delicious insectivore ground meal mixed with water and stirred to the consistency of peanut butter. Whether it’s the sound of the spoon tapping the bowl or the scent of the food, Danny’s nose begins to twitch and he lumbers to his feet, ready to roll. “He wakes up rarin’ to go,” said Vicki, as he knows he gets to go for a walk or a cart ride around the Safari Park.

DYNAMIC DIGGING DUO

Danny enjoys his forays out in the Safari Park with his devoted trainers. It makes perfect “scents.”

Danny has been trained, and is now eager, to step into his harness, walk onto a scale, and amble up a ramp into the cart. But how do you manage 110 pounds at the end of a leash? Donna explained that they are good at “reading his postures” and staying ahead of his reactions. “We have learned what motivates him and what startles him over the years, and we act accordingly.” On walks, he is sniffing the entire time. “He’s all about food, moving, or get out of my way,” she added. Visitors may encounter him strolling around The Grove picnic area near Tembo Stadium, Animal Encounters at African Outpost, or on a Behind-the-Scenes Safari. “Aardvarks are interesting and important animals that we want people to learn more about,” said Vicki. “They are rare in zoos, so having a ambassador aardvark is a special experience.”

DIGGING LIFE

Zola at the Zoo takes full advantage of the soft substrate in her enclosure. Excavating is a way of life!

Zoo visitors will also have the opportunity to meet an aardvark up close: Zola is in training to be an animal ambassador at Conrad Prebys Africa Rocks, opening in summer 2017. At 1 year old and about 120 pounds, the rotund creature has already learned to “station” for nail filing and lotion application on her feet, said Cari Inserra, lead animal trainer. She also stands at attention as her harness is put on, perhaps anticipating the delicious mealworms and avocado to come. Zola lives in an off-exhibit area with plenty of loose soil, which she happily burrows into. “We had to get a plumber with a long rod camera to see how long Zola’s burrow was!” said Cari. “Zola can sleep a good six feet in, so we can’t ‘bother her’ while she’s sleeping.” But if she’s snoozing above ground, the wafting scent of her food will send her nose snuffling. Whether it’s Danny at the Park or Zola at the Zoo, meeting an aardvark is something you’ll “dig”!