Zoo InternQuest is a seven-week career exploration program for San Diego County high school juniors and seniors. Students have the unique opportunity to meet professionals working for the San Diego Zoo, Safari Park, and Institute for Conservation Research, learn about their jobs, and then blog about their experience online. Follow their adventure here on the Zoo’s website!

Some people find snakes and lizards to be creepy or frightening, but not Rachael Walton a reptile keeper here at the San Diego Zoo. Ms Walton’s day consists of caring for nearly 200 reptiles, ranging from tiny tortoises to massive rattlesnakes. Here are just a few of the reptiles that Ms. Walton introduced us to:

This is Mickie, a woma python. He has a special “job” at the Zoo; he works with the education department as an Animal Ambassador. Mickie helps to teach the public, particularly children, about the importance of reptiles and conservation.

In the jungles of South America, the male caiman lizard’s bright red heads help females find them, so that they can mate. The caiman lizard got its name from its resemblance to the caiman, which is a species of crocodilian. Being that caiman lizards are calm and fairly docile around people; this species is commonly farmed for their pelts. Fortunately, the lizards have a healthy population and are not endangered.

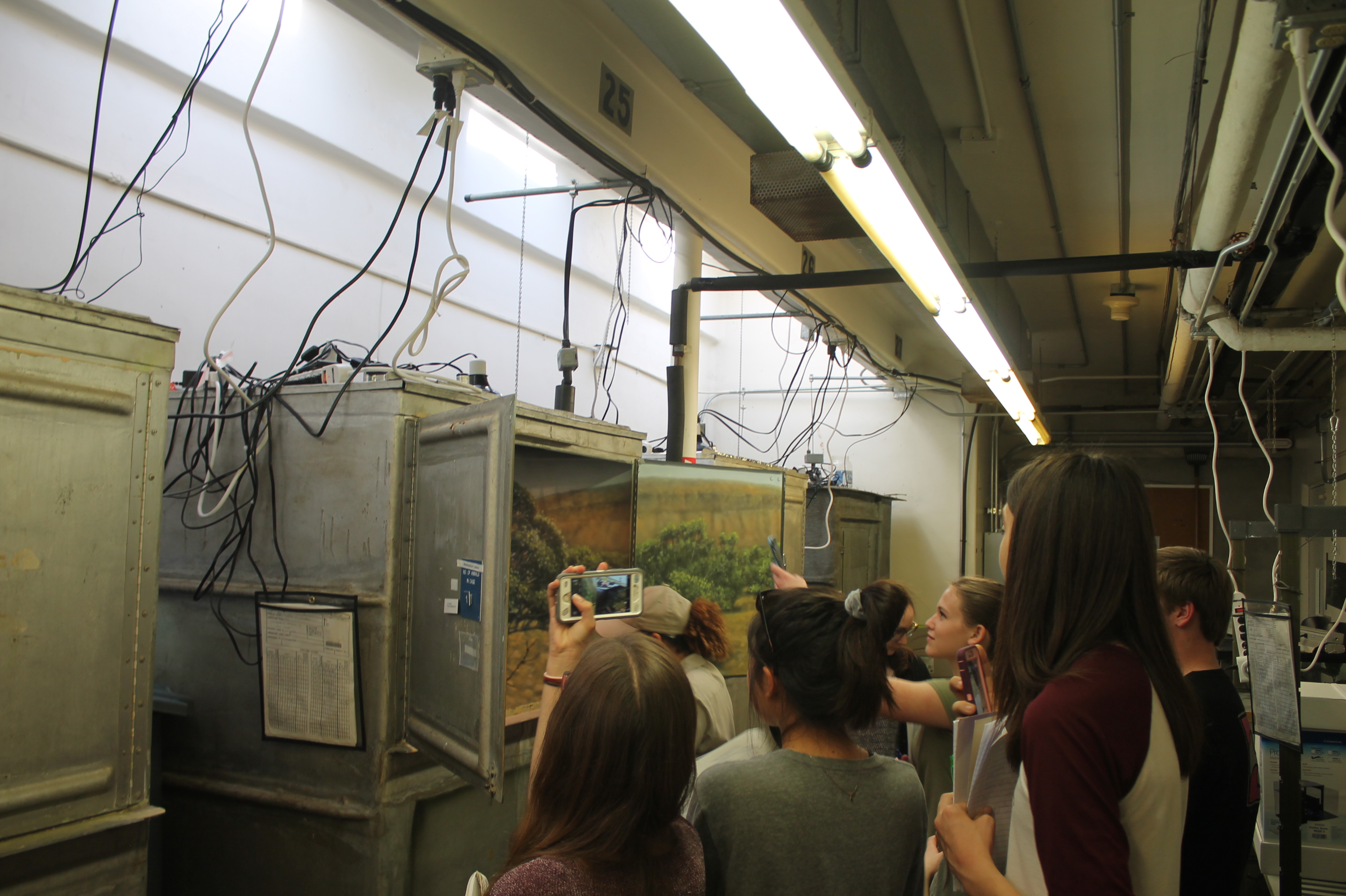

The reptile house is a series of climate-controlled corridors housing species that live in similar climates. Some corridors are hot and dry while others are warm and humid. Pictured above is a view down one of the corridors; on the left are reptiles that are not currently on exhibit, and on the right are the backs of the exhibits that the public can view.

Here Ms. Walton is showing us how the keepers access the exhibits to clean and give the animals food and water. Most of the animals that are out on exhibit rotate so that one animal is not out for an extended periods of time. The exhibits are modeled to resemble the animals’ natural habitats.

Sometimes people try to smuggle reptiles into the United States in order to sell them on black markets, but if they are caught at customs, the animals sometimes are sent to the Zoo. This king cobra is one of these animals. It was confiscated along with two other cobras that were being transported in Pringles cans. An aggressive species, the cobra flares its hood even at a young age.

Safety is a priority among the reptile keepers. That’s why all venomous snakes are marked with a bright red tag. In the case of a bite, the tag outlines treatment for the wounds and the appropriate anti-venom. When the keepers have to remove a venomous snake from its holding, they use gloves and a hook (as pictured) to minimize the possibility of a bite.

Of the venomous species that reside at the Zoo, the rattlesnakes are the most numerous. Some of the species at the Zoo include the eastern and western diamondback and the Mexican lanceheaded rattlesnakes. Rattlesnakes do not keep the same rattle throughout their life; the snakes will shed their rattle, or it can even fall off if it gets bumped against something.

This brightly colored turtle is about 15 years old. Unlike many turtles, the golden coin pond turtle keeps its colors for the duration of its life. The turtle’s round head is a bright yellow and looks just like a coin sitting at the bottom of the pond. Unfortunately, rumor has it that eating this turtle would cure cancer, which has caused this turtle’s population to be decimated.

This little turtle is southern California’s only native species, the western pond turtle. Pet turtles released into the wild displace the naturally timid western pond turtle from its habitat. Bullfrogs are also a threat, as they eat juvenile turtles. Invasive species to Southern California are most likely the cause of the declining population of this uniquely Californian animal.

These two tortoises are endangered species native to the island of Madagascar. On the left is the flat-tailed spider tortoise, and on the right is the radiated tortoise. The tortoises have been a part of the native people of Madagascar’s diet and for generations were sustainably hunted. Commercialization of the tortoise trade has led to the drop in wild population.

These four baby tortoises are all different species! The reptile house is home to about 1,650 animals, some of which are endangered, like the Madagascar tortoise, and others that have stable populations in the wild, like anacondas. Some of these tortoises will remain at the Zoo, and others will be sent to zoos around the country to keep populations in managed care diverse.

Believe it or not, this Fiji iguana can change its color. Although it only changes in shades of green, it is an “emotional” reptile, like chameleons. These lizards will change colors to display distress or anger, to signal to females to mate, and to warn other males not to get to close. The Fiji iguana has been impacted by deforestation, making the Zoo’s work with them all the more important.

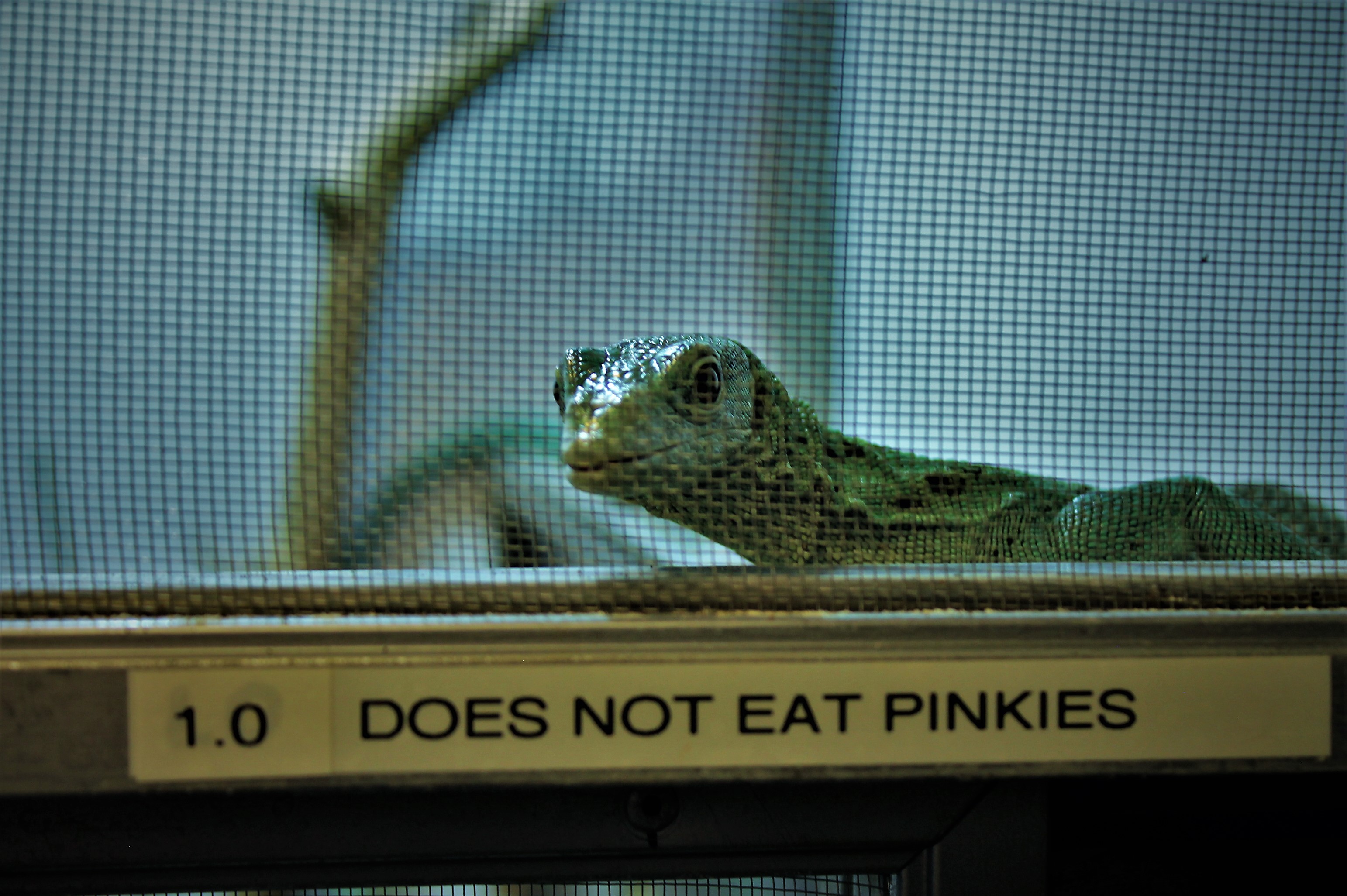

Here is one of the Zoo’s many monitor lizards. Ms. Walton is currently working with one of the female monitors to train it to become an Animal Ambassador; however, she is presented with a challenge as the monitors are skittish by nature. The sign underneath the enclosure does not refer to pinkie fingers, but rather newborn mice, which are pink. Monitors are omnivorous, eating a diet of both plants and animals.

You may be wondering how reptiles are transported from zoo to zoo. The answer: by air. Carefully packaged and marked, reptiles can be shipped across the country. Delta is the only airline that will transport venomous snakes, which are packaged securely in several boxes. FedEx also has a “ship your reptile” program.

The Zoo keeps a stock of antivenom for each venomous species of reptile in their care. Ms. Walton described venom as a recipe. Only a few different toxins are produced by all snakes in different amounts, which in turns, causes different effects. The staff periodically has drills in order to be prepared should a bite occur, which thankfully, has not happened within the last decade.

The time spent with Ms. Walton provided a glimpse into the incredibly diverse world of reptiles. The various adaptations are amazing: from thermal sensing glands, to tails that look like worms, to the ability to change colors. Although some of the them look like prehistoric creatures, reptiles play an important role in the world today, and their conservation is just as important as any other animal’s.

James, Photo Journalist

Week Three, Winter Session 2018