Zoo InternQuest is a seven-week career exploration program for San Diego County high school juniors and seniors. Students have the unique opportunity to meet professionals working for the San Diego Zoo, Safari Park, and Institute for Conservation Research, learn about their jobs, and then blog about their experience online. Follow their adventures here on the Zoo’s website!

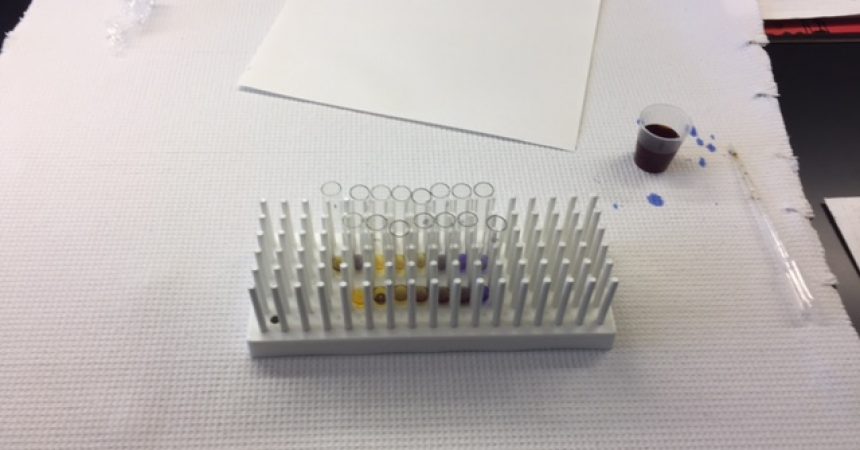

How do you find out if a rhinoceros is pregnant? Through a pregnancy test? Well, not exactly. This week, interns were given the opportunity to meet Christopher Tubbs, a Scientist in the Reproductive Physiology division at the Institute for Conservation Research. More specifically, Dr. Tubbs frequently studies how chemicals in the environment affect the reproductive health of animals. He explained that by taking fecal or urine samples, over the course of a few weeks you can determine if an animal is pregnant, cycling, or in estrus. This is extremely valuable information when it comes to sustaining breeding programs in managed care facilities. If the Zoo knows when a female is cycling, then they would be able to partner that female with a suitable male, which ultimately increases the odds of pregnancy.

How do you find out if a rhinoceros is pregnant? Through a pregnancy test? Well, not exactly. This week, interns were given the opportunity to meet Christopher Tubbs, a Scientist in the Reproductive Physiology division at the Institute for Conservation Research. More specifically, Dr. Tubbs frequently studies how chemicals in the environment affect the reproductive health of animals. He explained that by taking fecal or urine samples, over the course of a few weeks you can determine if an animal is pregnant, cycling, or in estrus. This is extremely valuable information when it comes to sustaining breeding programs in managed care facilities. If the Zoo knows when a female is cycling, then they would be able to partner that female with a suitable male, which ultimately increases the odds of pregnancy.

An extremely important variable in reproductive health are environmental chemicals. Mr. Tubbs acknowledges that chemicals in the environment can negatively affect an animal’s hormones. To figure out which chemicals are harmful, lab technicians must isolate receptors, which are molecular structures in the body that respond to a certain neurotransmitter, hormone, chemical, etc, from pieces of tissue. Once the receptors are isolated, researchers can then study how well they respond to the chemicals in question. If the chemicals interact well with the receptors, then it may be harmful to the animal. The information gained during these studies can significantly increase the chance of survivability for many animals. For example, Dr. Tubbs once studied the effect diet had on rhinoceros fertility. After further research, he and his team were able to determine that the current rhino diet was indeed causing fertility issues. Since the study was completed, the Zoo has since changed the rhinos diet, and now females who had previously never been pregnant are expecting.

Dr. Tubb’s lab has worked on many conservation projects affecting species around the globe. Here in California there are many endangered species who need our help, but one in particular stands out; the California condor. This breathtaking species has an average wingspan of nine feet and is the largest bird in North America. Since the early 20th century, the birds’ population steadily declined until there were only 22 condors left in the wild. Given these dire circumstances, the remaining birds were captured and taken into captivity to save the species. After years of breeding, many condors have been reintroduced into the wild, and now there are over 400 condors alive today. However, the condors’ threats are far from over, as lead poisoning and microtrash consumption are still killing the birds. The reproductive physiology department is now concerned over the effect of marine mammal carcass consumption has on condor health. Currently, researchers are testing how different chemicals in fish, marine mammals, etc respond to condor receptors. This research has the potential to save hundreds of condors, or even the species as a whole. If the lab discovers a chemical that reacts with condor receptors, then the Zoo can implement a training program to deter the condor from consuming that specific species.

To help animals being affected by chemicals in the environment, the average person can stop flushing pharmaceuticals down the toilet (or any drain, for that matter), limit chemical use and stop using lead bullets. Why, lead bullets, you may ask? Unfortunately, when lead bullets puncture an animal, fragments of the bullet disperse across the body. If an animal eats the carcass, they may get lead poisoning. California condors are particularly susceptible to lead poisoning since they are scavengers. To help protect animals against chemical harm, take a pledge to reduce your chemical use, refrain from flushing pharmaceuticals down drains, and never use lead bullets. You can also help educate others about the importance of reducing chemicals in the environment. Remember, the animals are counting on us!

Sarah, Conservation team

Week Two, Winter Session 2017