Frog nanny is not an official job title, but it’s been my reality this year. I’m the “nanny” for some 1,176 healthy mountain yellow-legged frog (MYLF) tadpoles. This iconic California species is one of the most endangered frogs in North America. San Diego Zoo Global has been involved in the MYLF recovery program since 2009, and captive breeding has been an important component of our efforts to re-introduce froglets into their natural habitat in the Sierra Mountains. However, with little information on MYLF life history, the care and reproduction of these frogs in captivity presents many challenges.

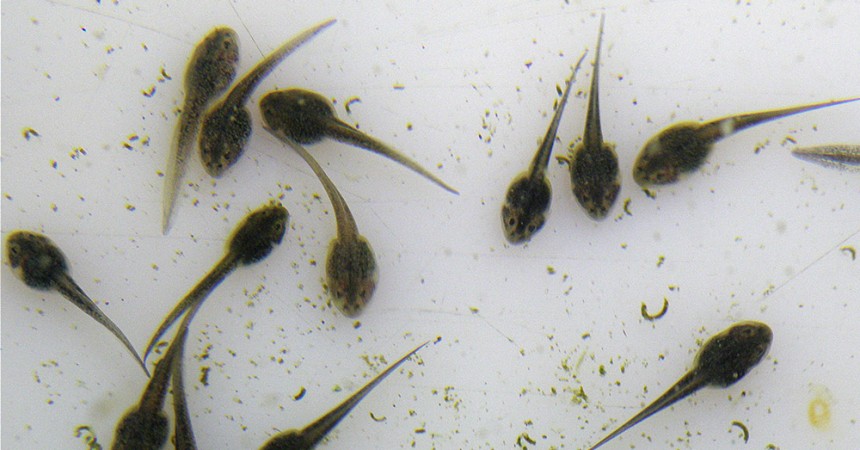

I have been working on this project full-time since last October. As I enter the lab and look into the 100-gallon containers holding the result of this years’ extremely productive breeding season, a feeling of excitement and nervousness comes over me. It takes about a month and a half for MYLF embryos to hatch out into free-swimming tadpoles, and in the meantime, they require daily preening. Early in the breeding season, I start my day by counting and cataloging over 1,800 embryos. Something like picking ticks off a chimpanzee, this entails cutting through the surrounding egg jelly and extracting any unfertilized or dead embryos from neighboring healthy ones. Sitting at the dissecting microscope, I examine and record what stage of development each embryo has reached every day. By the afternoon, I am all but cross-eyed. I walk around with constant images of beautifully formed black spheres in my mind’s eye. As the embryos grow and thrive, the stress of getting them through the early stage of development is taken over by concerns for stage two of tadpole rearing.

So what is stage two? We begin by focusing on what tadpoles need. MYLF tadpoles require cold, clean water, constant feeding, and plenty of space to grow. Like most infants, tadpoles are voracious eaters and require a constant supply of food. If too much food is offered, it accumulates in the tank, causing water quality issues. Too little food, and big brother Jake might start nibbling on his smaller sibling Fred. Cannibalism is not uncommon in amphibian species, so all I can do to stop Jake from eating his brothers and sisters is make sure I feed him enough.

Amphibian nutrition is a work in progress, and little is known of individual species’ requirements. This year, I have gone from reproductive physiologist to dietician. Researching amphibian nutrition is complicated by the specific needs of each life stage. Luckily, I have a supporting team of professional nutritionists and a wealth of knowledge and years of experience, courtesy of Brett Baldwin and David Grubaugh, amphibian/reptile keepers at the Zoo.

Controlling water quality is another daily necessity. The difference between clean and pristine can be subtle, and can affect growth and development in ways that may not be apparent until it is too late (like during metamorphosis). Armed with the HACH colorimeter DR-900, a small team of us (Nicole Gardner, senior research associate; Bryan King, research associate; me; and our weekly volunteers, Jaia Kaelberer, Janice Hale, and Jim Marsh) conduct daily screenings of the water in which our tadpoles live. Based on data we have collected on the water quality in MYLF habitat, we have specific parameters to which we can set our water standards in the lab.

They say “be careful what you wish for.” This year, we wished for a handful of MYLF egg clutches to be laid and for a couple of hundred embryos to survive. Instead, we got almost 2,000 eggs! As they grow, we become faced with a new challenge—overcrowding. To my relief, the solution becomes clear; together with our partners at the US Geological Survey and the Department of Fish and Wildlife, we decide to split our bountiful cohort of tadpoles into smaller groups. At the end of May, 711 lucky tadpoles made their triumphant way back to the wild, and 400 of their brothers and sisters stayed here with us. They will be “headstarted” and returned to the wild as froglets.

Everyone involved in this project lives and loves every moment. There is nothing more satisfying than watching a life form grow and thrive under your care. This year’s breeding season has exceeded all our expectations. If we take into account that less than one percent of MYLF tadpoles are estimated to survive to metamorphosis and only an estimated 200 adults remain in the wild, everyone currently involved in this project holds the key to this species’ survival. That can be stressful, but it is also a humbling honor. I am happy to speculate that this is going to be a good year for our MYLF program, and that I will have the chance to be part of their journey back to nature.

Natalie Calatayud is a research associate at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. Read her previous blog, Rocky Mountain High: Boreal Toads Going to a Place They’ve Never Been Before.